Why Did They Do It That Way? Medicaid Financing

Author

- NAMD Staff

Focus Areas

Related Resources

As of November 2024, Medicaid and CHIP provided health coverage for almost 80 million people. Although the services covered by Medicaid vary across states and territories, all Medicaid agencies provide access to a range of inpatient, outpatient, long-term care, and pharmacy services for people who are eligible and enrolled in the program. Financing these services and accurately projecting future costs is a core component of how states, territories, and the federal government administer the Medicaid program.

How is the Medicaid program financed?

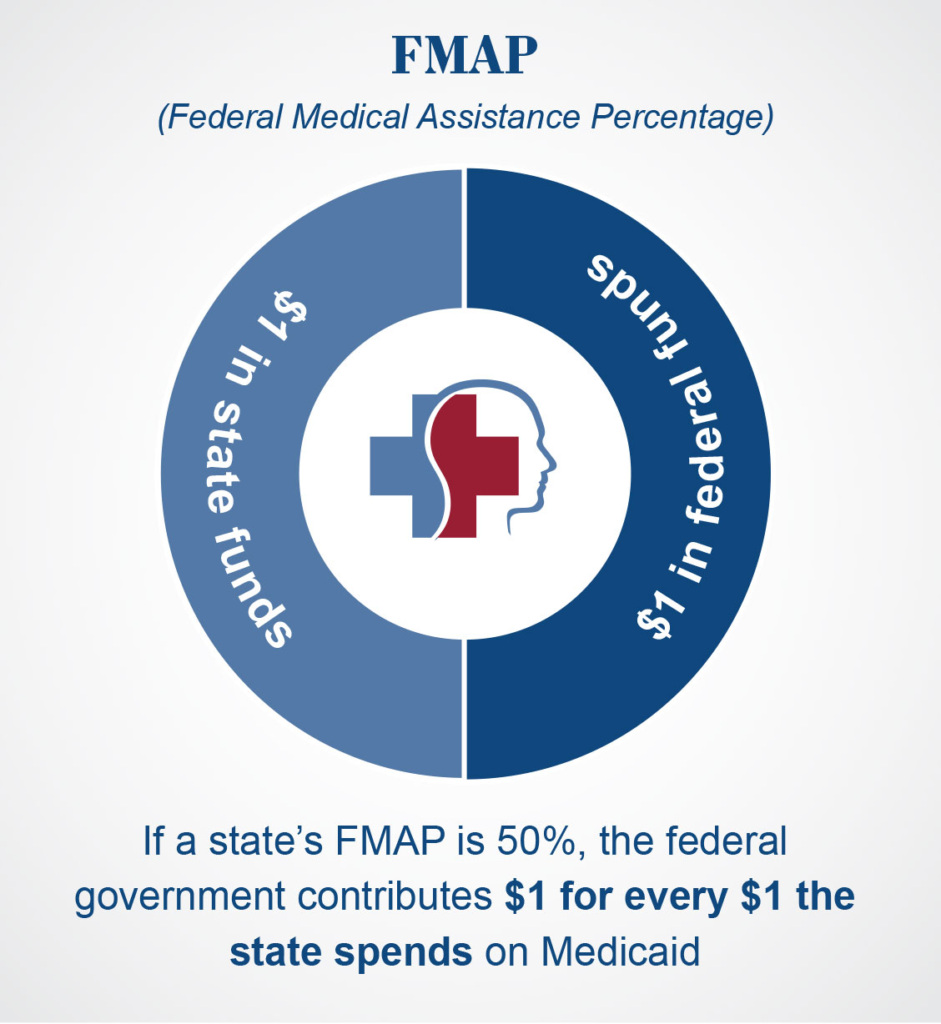

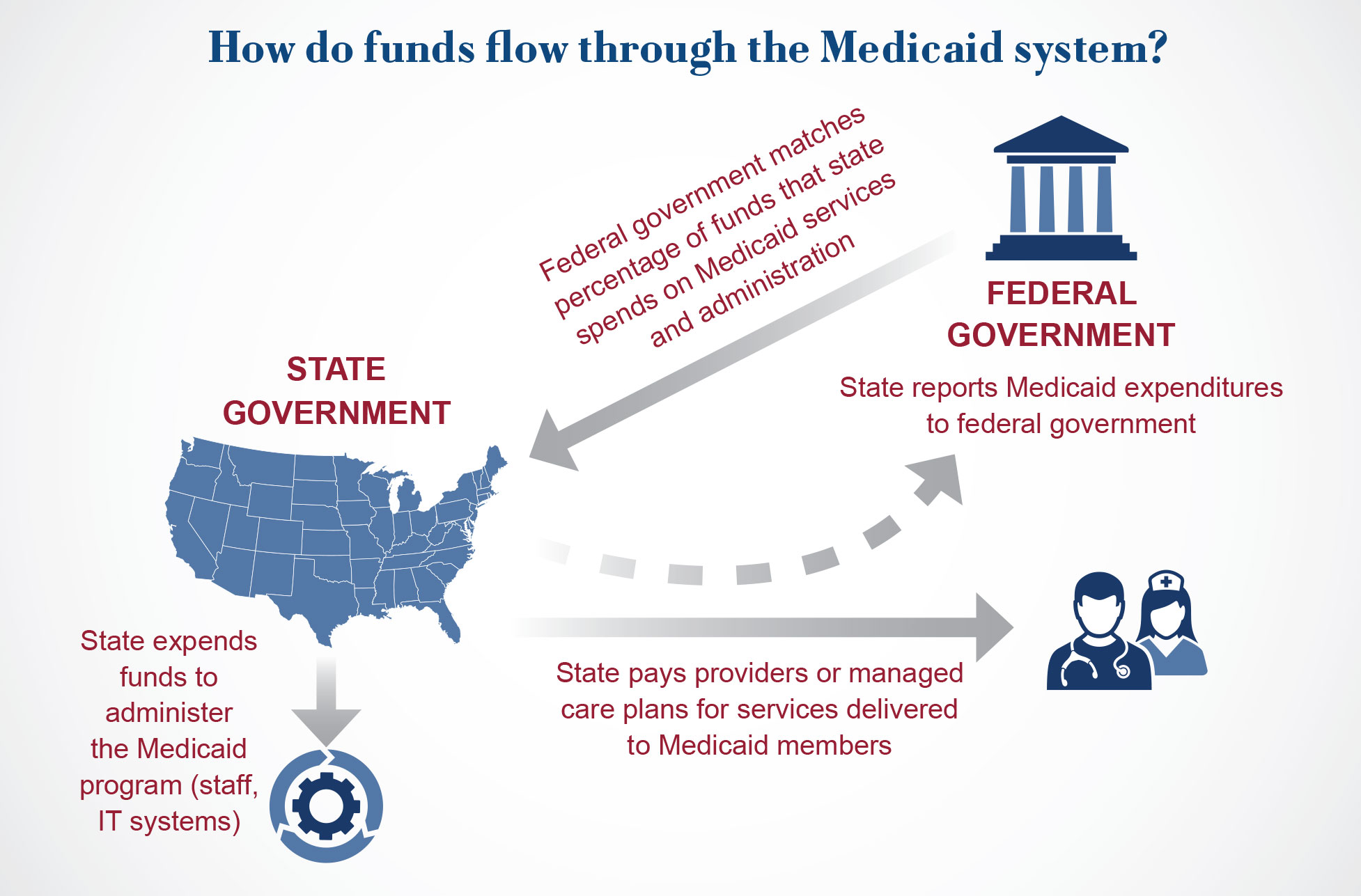

Unlike Medicare, which is run by the federal government, Medicaid is jointly financed and jointly administered by states, territories, and the federal government. Since the Medicaid program was created in 1965, the federal government has matched state spending on Medicaid services and other costs by contributing a certain percentage of funds. This percentage – which is called the federal medical assistance percentage, or FMAP – is calculated using a formula defined by Congress that compares each state’s rolling three-year average per capita income to the United States’ per capita income. This results in states with lower per capita incomes receiving a higher contribution rate and states with higher per capita incomes receiving a lower contribution rate; all states have a maximum FMAP rate of 83 percent and a minimum FMAP rate of 50 percent for this base FMAP.

Medicaid’s financing structure can be traced to its roots in the public assistance system. In 1950, Congress passed a set of amendments to the Social Security Act to provide states with federal matching funds for certain medical services provided to individuals who were receiving cash assistance. Then, in 1960, the Kerr-Mills Act created the Medical Assistance for the Aged program, which gave states matching payments for health care services for certain older adults. When Congress created the Medicaid and Medicare programs through the Social Security Amendments of 1965, they retained the federal-state financing structure of the Kerr-Mills Act and adopted the FMAP formula that is still used today.

The federal match rate for most Medicaid-covered services follows this statutorily defined formula. However, there are important exceptions, including different FMAP rates for certain populations, providers, and activities. Congress often uses higher – or “enhanced” – FMAP rates to incentivize states and territories to cover certain services or populations or, alternatively, FMAP reductions to penalize states for not complying with federal requirements. For example, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 created a time-limited FMAP increase for activities that “enhance, expand, or strengthen” home and community-based services. Congress has also used FMAP enhancements to provide broader fiscal relief to states and territories, including through a disaster recovery FMAP adjustment.

Importantly, the five U.S. Territories – American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands – have a different Medicaid financing structure than the states. The territories’ FMAP rate is set by Congress, instead of using the FMAP formula defined in statute. Historically, the Territories’ FMAP rates were all set at 55%. In 2023, Congress permanently increased the FMAP rate to 83% for American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, and temporarily increased Puerto Rico’s FMAP to 76%. Additionally, the territories’ federal funding is capped, meaning that once the territories reach their funding allotments each year, they must use entirely local funds to pay for Medicaid-covered services or take steps to manage the lack of additional federal funds, such as reducing the benefits they cover or pausing payments to providers.

How do states and territories fund the “state share” – or nonfederal portion – of Medicaid costs? According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), in 2018, 68 percent of state share came from state general revenue (which includes state income tax, sales tax, property tax, and fees), while the remaining 32 percent came from local government, taxes on providers, and other sources. As explored below, both federal match and state share play important roles in a state’s budget.

Why is Medicaid important to state and territory budgets?

Medicaid plays a significant role in state and territory budgets. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), Medicaid was the largest total spending category for states in FY2024, representing about 30 percent of total state expenditures from all sources. However, it is important to note that federal funds – including federal Medicaid matching funds – are included in this calculation; when looking only at state general fund expenditures, Medicaid’s footprint shrinks, representing 18.7 percent of general fund expenditures. This is still a substantial share of state resources, coming second only to education, meaning Medicaid plays a central role in state budget processes.

How does the state budget process work?

How do states and territories create their budgets, and how does Medicaid factor into these processes? During the budget process, state and territory legislatures appropriate funds to the programs and services – including education, law enforcement and corrections, public assistance programs like SNAP and TANF, transportation and infrastructure, and Medicaid – that they wish to provide. This means that the state or territory budget determines what programs and services are available to residents of the state.

There are important constraints on state and territory budgets. Most states operate under balanced budget requirements, so, unlike the federal government, they cannot spend more than they collect in revenue. Additionally, states and territories have many costs each year that must be paid, like state employee pensions and debt payments, or cannot easily be scaled back, like K-12 education and corrections.

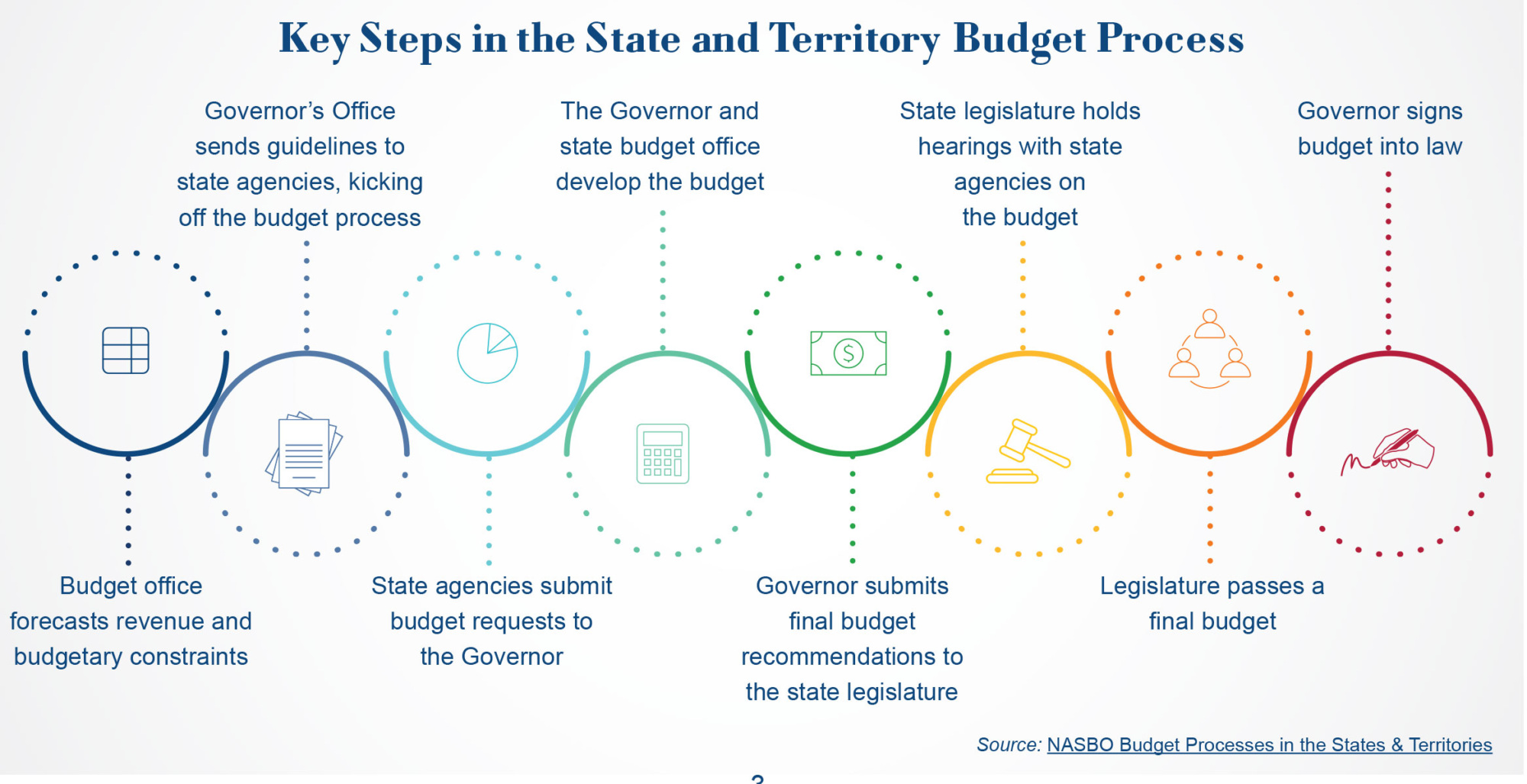

Because the state budget drives programs and services, creating the state budget is one of the most important tasks for the state legislature and governor each year. Generally, the Governor’s Office will first work with state agencies to develop a set of budget recommendations to the state legislature. During this process, the Medicaid or health and human services agency’s Chief Financial Officer (CFO) will typically work with the state budget office (and, in many states, with the legislature) to forecast Medicaid costs over the next fiscal year. This is a challenging and complex process, as the state needs to accurately predict how many people will be enrolled in Medicaid, what services they will utilize, and how much these services will cost, along with broader economic factors and market pressures like inflation. Medicaid agencies may also submit requests for new funding to implement new services, comply with federal requirements, or make changes to eligibility groups. Conversely, the Governor may recommend reducing Medicaid funding to account for a challenging state fiscal environment or to fund other policy priorities. Because Medicaid accounts for such a significant share of states budgets, reductions in Medicaid spending are often necessary during broader economic fiscal downturns.

The Governor’s budget recommendations typically serve as the starting point for the state legislature’s work on the budget. The legislature will review the Governor’s request, hold hearings with state agencies and other stakeholders, and develop legislative text. State legislators’ priorities may differ from the Governor’s, so it is not uncommon for the legislature’s budget bill to diverge substantially from the Governor’s budget recommendations. After the legislature passes a budget, it is then sent to the Governor to be signed into law (or vetoed, if the Governor opposes the budget). Once a budget is passed by the legislature and signed into law by the Governor, it becomes the official budget for the corresponding fiscal year.

This process typically takes a full year to complete. Thirty states and the District of Columbia operate on an annual budget cycle, meaning that they pass a budget each year appropriating funds for the next fiscal year. The remaining twenty states use two-year budgets, which appropriate funds for the next two fiscal years. State legislatures can pass supplemental appropriations bills throughout the year to account for unexpected costs or to fund new legislation, but the state budget is carefully crafted to account for costs over the budget cycle.

What factors impact Medicaid spending?

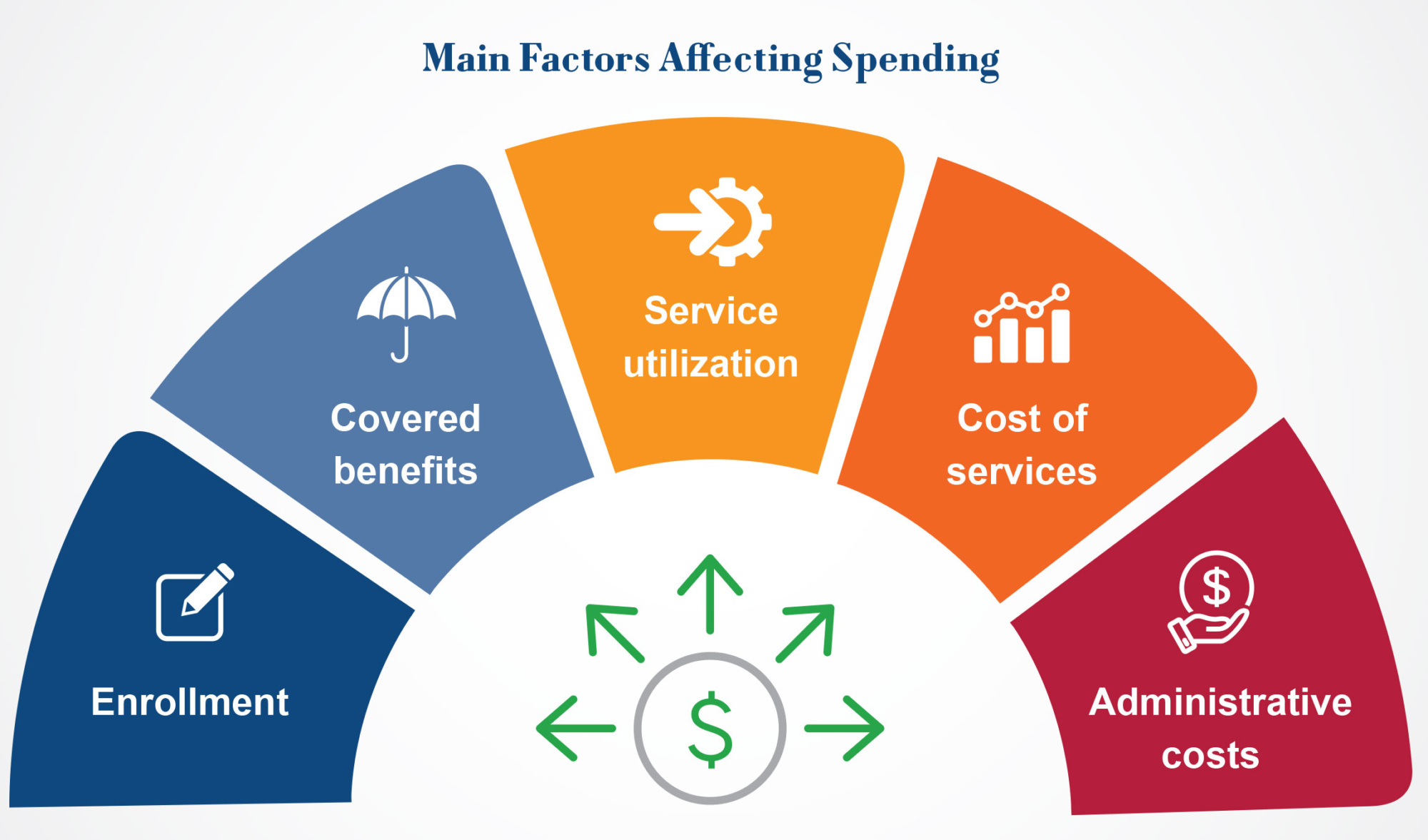

Spending on the Medicaid program varies across states and territories and looks different from year to year. Ultimately, spending on Medicaid services is determined by the number of people enrolled in a Medicaid program, the amount and type of services they utilize, and the cost of these services. Medicaid agencies must also account for the costs required to administer the program, including staff and IT systems.

Enrollment

Enrollment is a major driver of Medicaid spending. Under federal regulations, states are required to cover certain mandatory eligibility groups, including low-income children, low-income pregnant women, certain parents and caregivers, and individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income. States have the option to cover other eligibility groups including people with high medical expenses, people who need certain long-term care services, and low-income adults who do not have children.

Importantly, Medicaid spending is impacted not just by the number of people enrolled in the program, but also by the health needs of the people who are enrolled. Medicaid members who are eligible on the basis of age or disability tend to have significantly higher health care costs than children or adult Medicaid members who do not have a disability. This is because older adults and people with disabilities tend to need more health care services and higher cost services, including long-term care, and Medicaid is unique among payers in its coverage of services for these populations.

Medicaid is considered a “countercyclical” program, meaning that Medicaid spending increases during economic downturns. This occurs because Medicaid eligibility is partially based on income, and during economic downturns, more people qualify for the program due to lower income or loss of employment. To help account for this, Congress increased the FMAP rate during both the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2007 – 2009 recession, channeling increased federal funds to states and territories.

Covered benefits

Under federal law, Medicaid agencies must cover a set of mandatory benefits, including inpatient and outpatient hospital services, nursing facility services, lab and x-ray services, and physician services. In addition to these mandatory benefits, states and territories can choose to cover or not cover a wide range of optional benefits and waiver services, including prescription drugs, physical therapy, home health care, eyeglasses, and dental services.

The extent to which a state or territory covers optional benefits and waiver services can have substantial impacts on spending. Although covering optional benefits typically increases program costs, some optional benefits can help defray the costs of other more expensive services. For example, all states cover some form of home and community-based services, which tend to be more cost-effective than institutional long-term care.

Service utilization

Within a state’s set of covered benefits, Medicaid spending is also impacted by the volume and intensity of services that Medicaid members utilize. Health care utilization is influenced by many factors, including an individual’s health care needs, where and how often they seek care, and the availability and accessibility of services. Medicaid agencies – along with Medicare and private health insurance companies – use care coordination and utilization management strategies like prior authorization and preferred drug lists to help ensure that Medicaid members are using clinically appropriate and high value services.

Costs of services

Finally, Medicaid spending is impacted by the amount that a Medicaid agency pays for a service. The cost of health care services is impacted by a wide range of factors, including broader market realities like labor costs, equipment costs, inflation, and competition. In a fee-for-service delivery system, Medicaid agencies pay directly for services delivered by providers to Medicaid member; generally, states set these fee-for-service payment rates by looking at variables like the provider types who can deliver the service, costs associated with delivering the service, geographic variation, and rates under other payers like Medicare. In a managed care system, Medicaid agencies pay a monthly capitation rate to managed care organizations, who then pay providers. Medicaid agencies work with their actuaries to develop these capitation payments and sometimes engage in competitive bidding processes or negotiations with their managed care plans. Under federal law, these capitation rates must be “actuarially sound,” meaning that they are projected to cover “reasonable, appropriate, and attainable” costs for covered members over the contract period.

Administrative costs

Outside of spending on Medicaid benefits, states and the federal government must account for the costs of running the Medicaid program. Medicaid agencies need staff to manage the day-to-operations of the program, including Medicaid eligibility processes, enrolling and reimbursing providers, and applying for authorities through the federal government. Medicaid agencies must also build complex IT systems to manage claims processing and eligibility and enrollment functions. State, territories and the federal government share the costs of these expenses; most administrative costs are reimbursed at a 50 percent FMAP rate, while costs of Medicaid IT systems are reimbursed at a higher rate (90 percent for system development and 75 percent for system maintenance).

What factors will impact Medicaid spending over the coming years?

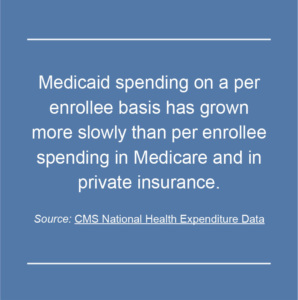

In the United States, health care spending across payers has grown dramatically over the past several decades, with per capita expenditures reaching $14,570 in 2023. Research indicates that there are many factors driving increased health care spending in the United States, including price increases for inpatient and outpatient services, increased spending on prescription drugs, and the aging population. Notably, However, Medicaid Directors report concerns over budgetary challenges and fiscal pressures in their programs, along with broader state fiscal trends. What factors might impact Medicaid spending over the coming years?

Prescription drugs

Medicaid Directors report concern over the rising cost of prescription drugs. Under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, Medicaid agencies must cover almost all FDA-approved outpatient drugs from participating manufacturers in exchange for rebates that reduce the cost of these drugs. From FY2017 to FY2023, net spending on Medicaid prescription drugs increased by 72%, and is projected to continue to outpace inflation.

Much of this spending growth has been driven by the approval of new high-cost specialty drugs, many of which have list prices of over a million dollars. Blockbuster drugs – defined as pharmaceutical products with over $1 billion in annual sales – can drive significant breakthroughs for health outcomes but also create budgetary pressures for Medicaid agencies. For example, Medicaid agencies’ spending on GLP-1 medications like Ozempic and Wegovy almost doubled from 2022 to 2023, even though Medicaid is only required to cover these drugs for non-weight loss indications such as diabetes. As additional blockbuster and high-cost specialty drugs come to market, these cost pressures will continue.

Long-term services and supports

Medicaid agencies must plan for increased demand for long-term services and supports (LTSS). Medicaid is the United States’ primary payer for LTSS, including home and community-based services (HCBS) and institutional care like nursing facilities; according to KFF, Medicaid paid for 61% of total US spending on long-term care services in 2022. Demographic changes will increase the incidence of need for LTSS, with the U.S. Census Bureau projecting that the number of Americans ages 65 and older will increase from 58 million in 2022 to 82 million in 2050.

Over the past several decades, advocates and policymakers have worked to “rebalance” the care continuum to provide more home and community-based services, which are more cost-effective than institutional care and are preferred by older adults. These rebalancing efforts will become even more important as the United States’ population ages.

Utilization and price increases

Medicaid agencies report that increased utilization of services and prices of services are impacting program costs. Many of the factors driving utilization and price increases are affecting payers across the health care ecosystem; group and marketplace health plans have pointed to workforce shortages, other inflationary pressures on health care labor and supply costs, consolidation in the health care market, and increased utilization of mental health and substance use services as key drivers of cost growth. These broader market forces put upward pressure on Medicaid reimbursement rates and make it more difficult to forecast Medicaid spending during development of the state or territory budget. There are also factors unique to the Medicaid program that are impacting utilization; although Medicaid enrollment declined significantly after the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency’s continuous coverage requirement, Medicaid agencies report that members who retained coverage during the unwinding have significantly higher health care needs, resulting in increased spending per member.

Conclusion

Medicaid provides access to health care for millions of people, including low-income families, pregnant women, children with complex health care needs, single adults below certain incomes, individuals living with disabilities, and older adults. It also plays a role in supporting the health care system that serves all Americans. Over the coming decades, Medicaid and other health insurers will have to navigate new pressures on how they pay for care, including new treatments, an aging population, and broader health care market forces. A strong state-federal partnership, effective program management, and new payment strategies for cost drivers like prescription drugs will be crucial as states and territories weather these trends.

NAMD would like to thank the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) for their insights during the development of this brief.

Related resources

How Medicaid Provider Taxes Work: An Explainer

Medicaid’s Next Chapter

Stay Informed

Drop us your email and we’ll keep you up-to-date on Medicaid issues.