Why did they do it that way? Home and community-based services

Medicaid: The more you learn

Author

- Hannah Maniates

Focus Areas

Project

Read more like this

What are home and community-based services?

Long-term services and supports encompass the range of medical, personal care, and social services that may benefit an older adult, person with disabilities, or person with other chronic health conditions. The Administration for Community Living estimates that 69% of people will use long-term services and supports during their lifetime. Many different groups of people use long-term care, including older adults, people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD), people with physical disabilities, and people with mental health conditions.

Long-term care can be delivered in institutions, like a nursing facility, hospital, or intermediate care facility (ICF), or through home and community-based services (HCBS). HCBS include home health, adult day health, personal care services, case management, and other services that allow an individual to remain in their home or community instead of going to an institution for care. Over time – and in response to patient preference and advocacy – states and territories have worked to increase access to HCBS.

What is Medicaid’s role in the long-term care system? Although Medicare is the primary insurance system for older adults and younger people with disabilities, it provides very limited coverage for long-term care. In contrast, Medicaid covers both institutional care and HCBS. According to a recent KFF analysis, Medicaid paid for 54% of the $402 billion spent on long-term services and supports in 2020, and for 57% of national spending on HCBS. Individuals who are not eligible for Medicaid may pay for long-term care out-of-pocket, via private long-term care insurance, or through other federal payers like the Veterans Health Administration and the Indian Health Service, or may receive unpaid care from family or friends.

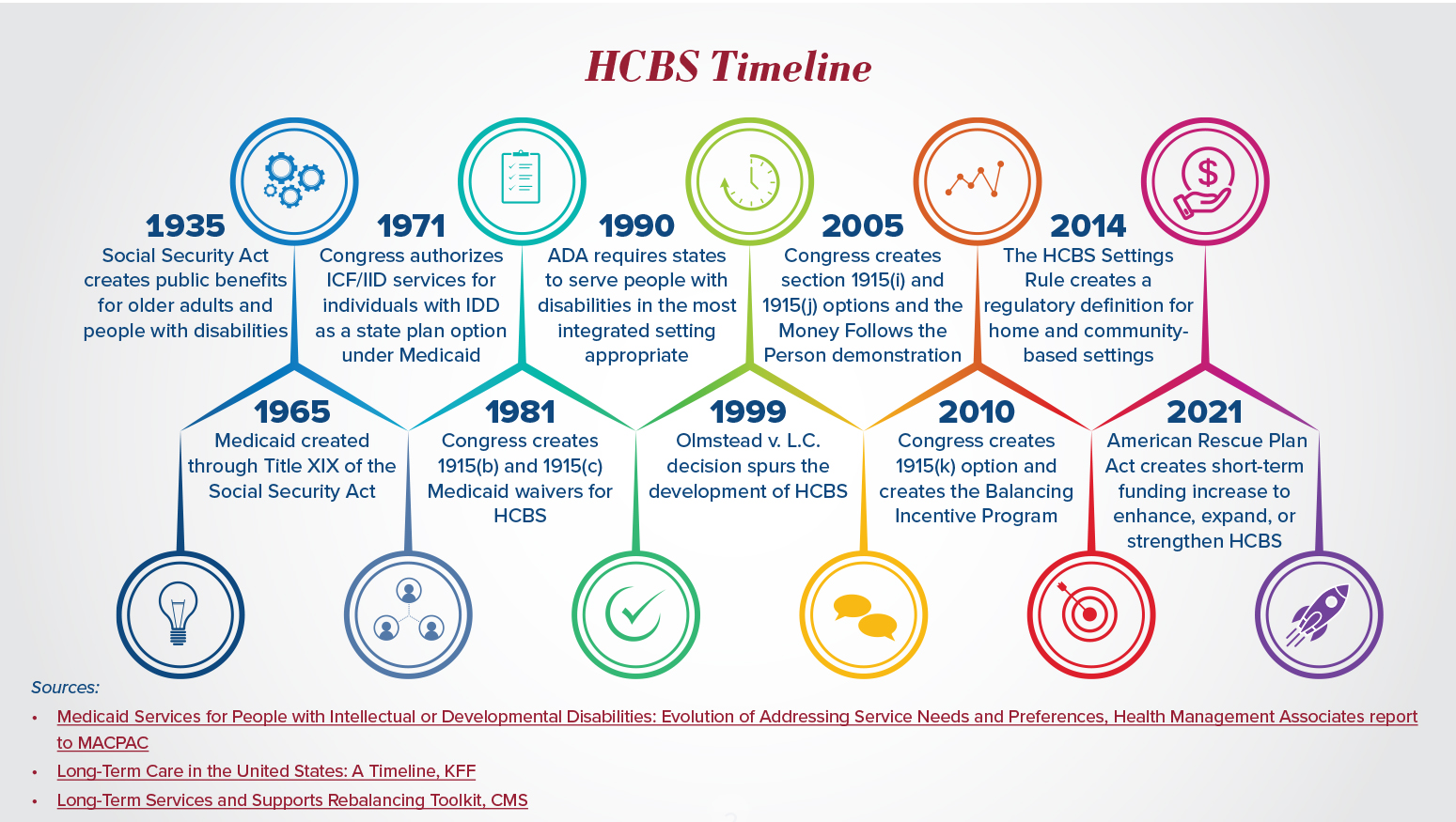

Like other parts of the health care system, the United States’ long-term care system has developed incrementally over time. Prior to the 1930s, long-term care was largely provided by family members, public almshouses, and hospitals. In 1935, the Social Security Act created assistance programs for older adults, leading to the proliferation of private “rest homes,” antecedents to modern day nursing homes. The 1950 amendments to the Social Security Act and the 1960 Kerr-Mills Act then spurred the development of long-term care facilities funded by states and the federal government; by 1965, approximately 60 percent of nursing home residents were paid for by states or the federal government.

In 1965, Medicaid was created through Title XIX of the Social Security Act. Per the Act, Medicaid programs were required to cover certain eligibility groups (including low-income older adults, people with disabilities, families with children, and blind people) and benefits (including nursing home care). Throughout the 1970s, Congress authorized states to cover additional long-term care services through Medicaid, including services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) and personal care services. And in 1981, Congress authorized Section 1915(b) and

(c) waivers that gave Medicaid agencies the ability to cover HCBS for individuals who are at risk of institutionalization.

Many of these coverage expansions were driven by advocacy from people with disabilities and their caregivers. One example is the Katie Beckett Waiver, which allows states to cover children under age 19 who have significant disabilities and are living at home. The Katie Beckett waiver was created in response to determined advocacy from Julie Beckett

on behalf of her daughter, Katie, who lived in pediatric intensive care after she contracted viral encephalitis as a baby. Katie and Julie Beckett went on to a decades-long career in advocacy, collaborating with other people with disabilities, caregivers, and organizations to spur significant expansions in Medicaid coverage of HCBS.

To this day, Medicaid regulations require states and territories to cover institutional care but not most HCBS. As a result of this “institutional bias,” Medicaid-funded long-term care services were historically primarily delivered in institutions; for example, in 1988, 88% of all long-term care service expenditures were spent on institutional care. How, then, have HCBS become the primary delivery model today?

Over the past several decades, disability rights advocates, family members, and state and federal policymakers have pushed for greater access to community-based care, resulting in major shifts in the delivery system. Some of these shifts created new legal protections for people with disabilities; in 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed, codifying protections against discrimination for individuals with disabilities. The ADA included an “integration mandate,” which prohibited the “unjustified segregation” of individuals with disabilities. This mandate was specifically applied to long-term care through the Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead v. L.C. decision, which states that a person with a disability must be served in the community when: 1) community-based services are appropriate to the individual’s needs; 2) the person does not oppose receiving services in the community; and 3) the state, territory, or local government can reasonably modify its services to deliver community-based care. Other regulatory shifts – such as the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, which created the Money Follows the Person demonstration, and the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021– created new fiscal resources for rebalancing efforts.

These changes were not a silver bullet, and states/territories still face challenges rebalancing their care continuums towards HCBS. However, sustained action by people with disabilities, their caregivers, providers, and policymakers has transformed the country’s long-term care system, with Medicaid spending on HCBS outpacing spending on institutional care in every year since 2013.

How do home and community-based services vary across states and territories?

Under federal Medicaid regulations, coverage of nursing facilities is mandatory while coverage of most HCBS is optional. This is often referred to as the “institutional bias” in Medicaid. Because of the optional nature of HCBS benefits, there is substantial variation across states and territories in eligibility for HCBS, covered benefits, and federal pathways.

How do HCBS look different across states and territories? Because HCBS are largely optional, there is significant variation in which populations are eligible for HCBS. According to a 2021 KFF analysis, nearly all states cover children with disabilities and working people with disabilities; about three quarters of states also cover individuals who are “medically needy,” meaning that they have high medical expenses that impact their financial stability, even though their incomes exceed normal Medicaid eligibility thresholds.

States and territories also apply different eligibility criteria to their HCBS programs. Eligibility for HCBS typically depends on both financial criteria, such as income, assets, and resources, and non-financial criteria. For non-financial criteria, states and territories use level of care assessments or functional assessments to assess an individual’s health and functional needs. Per federal law, many HCBS programs require that service recipients have level of care needs that would otherwise qualify them for institutional care.

There are also significant differences across states in terms of the services and benefits delivered under each HCBS program. All Medicaid agencies are required to cover home health state plan services, including nursing services, home health aide services, and certain medical supplies. Every state, however, has chosen to build on this federal floor by offering additional benefits to some eligibility groups, with specific benefits varying substantially across programs. Many states also apply limits to covered HCBS, like waiting lists.

What drives this variation? As with other parts of Medicaid policy, choices around the HCBS system are driven by policy priorities and constraints. A state may choose to prioritize various aspects of the HCBS system based off local need and stakeholder priorities; for example, one state may choose to expand eligibility for HCBS by raising income limits, while another state may instead choose to invest in a broader array of services for a smaller number of individuals. State and territory budgets are a key constraint on the provision of long-term care services. As of 2019, LTSS expenditures comprised about a third of total Medicaid expenditures, and these costs are projected to grow as the United States’ population ages.

There is also substantial variation across states in their proportion of long-term care delivered in institutions vs. through in the community. Older adults prefer HCBS and HCBS tend to be more cost-effective than institutional care, so why do we see this variation? The federal institutional bias is one driving factor; because institutional services are mandatory, states and territories may be forced to instead reduce HCBS during budget downturns, and it is more administratively burdensome to provide HCBS than institutional care. However, research indicates that the availability of HCBS is also impacted by a range of other factors, including state leadership, the strength of local advocacy organizations and lobbying groups, and Olmstead lawsuits and settlements. The availability of affordable housing also impacts efforts to rebalance the continuum towards HCBS, as individuals who lack stable housing typically must resort to institutional care.

What are the federal pathways for Medicaid coverage of home and community-based services?

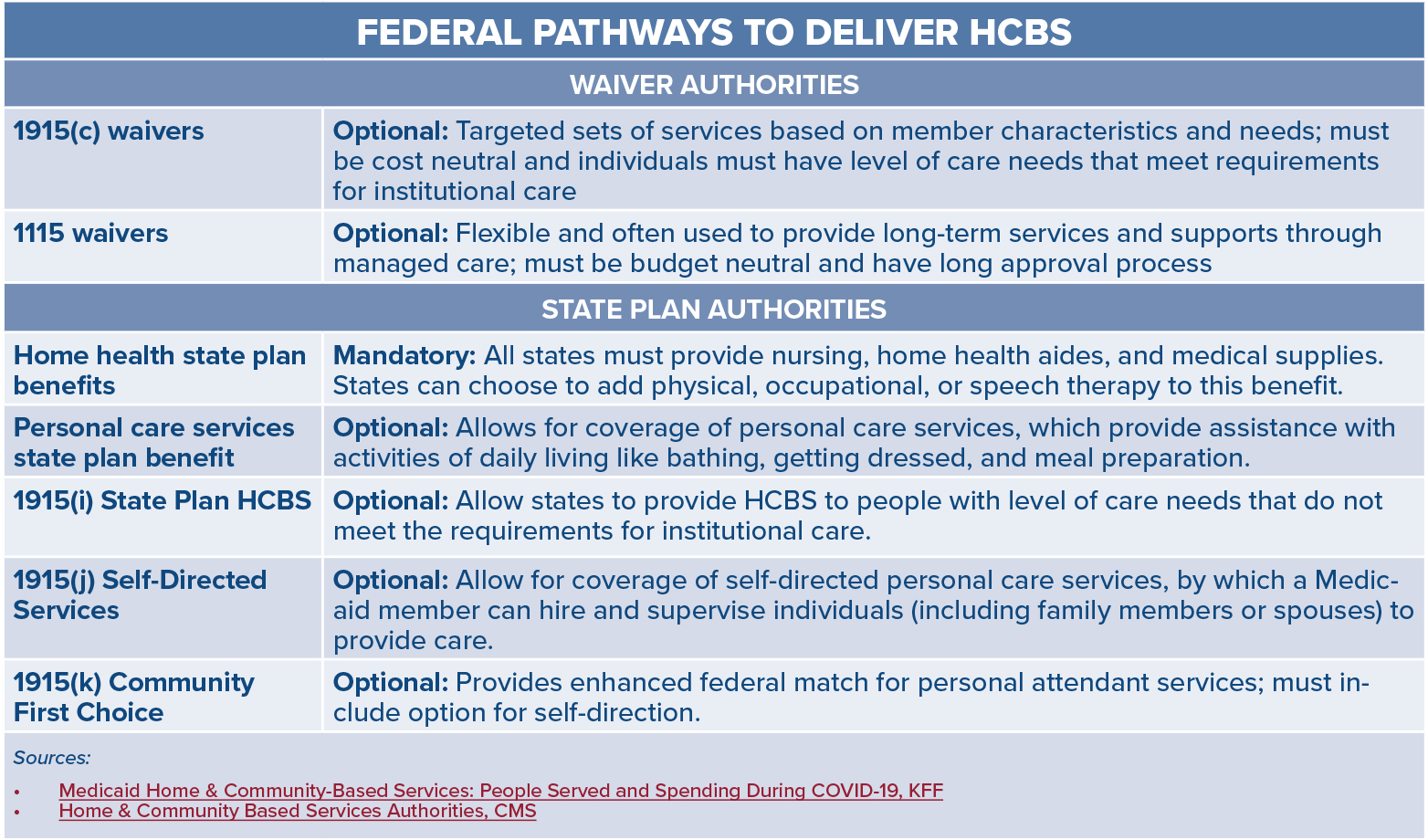

After setting a vision for which long-term care services to cover and for whom, states and territories must receive federal authority to provide these services and receive matching funds. Medicaid agencies can cover HCBS through state plan authorities, which are benefits that are available to all individuals who meet eligibility criteria, or through waiver authorities, which can be targeted to more narrow populations.

As of 2020, the majority of HCBS spending and services were delivered through 1915(c) waivers. Under 1915(c) waivers, Medicaid agencies can develop targeted sets of services based on member characteristics and needs, such as services for individuals with I/DD, traumatic brain injury (TBI), or mental health conditions. 1915(c) waivers also allow Medicaid agencies to use wait lists to manage costs and reduce fiscal risk. 1915(c) waivers, do however, come with additional federal requirements; these waivers can only serve individuals who have level of care needs that would meet eligibility criteria for institutional care and the waivers must be “cost neutral,” meaning that they don’t cost the federal government more money than would be spent in an institution. Many states also delivery HCBS through 1115 demonstration waivers, which are very flexible but come with strict budget neutrality requirements and long approval pathways.

HCBS can also be delivered through the Medicaid state plan. All states and territories are required to cover home health benefits, including nursing and home health aides, and the majority of states choose to provide personal care services as a state plan benefit. Almost every state also provides the option to self-direct services for at least some members. Self-direction honors individual autonomy by allowing Medicaid members to hire and supervise individuals, including family members or spouses, to provide certain types of care.

In practice, most states use a combination of waivers and state plan authorities to deliver HCBS. By layering different federal pathways, states and territories can tailor HCBS services to local need, policy priorities, and the state fiscal landscape.

How do states deliver home and community-based services?

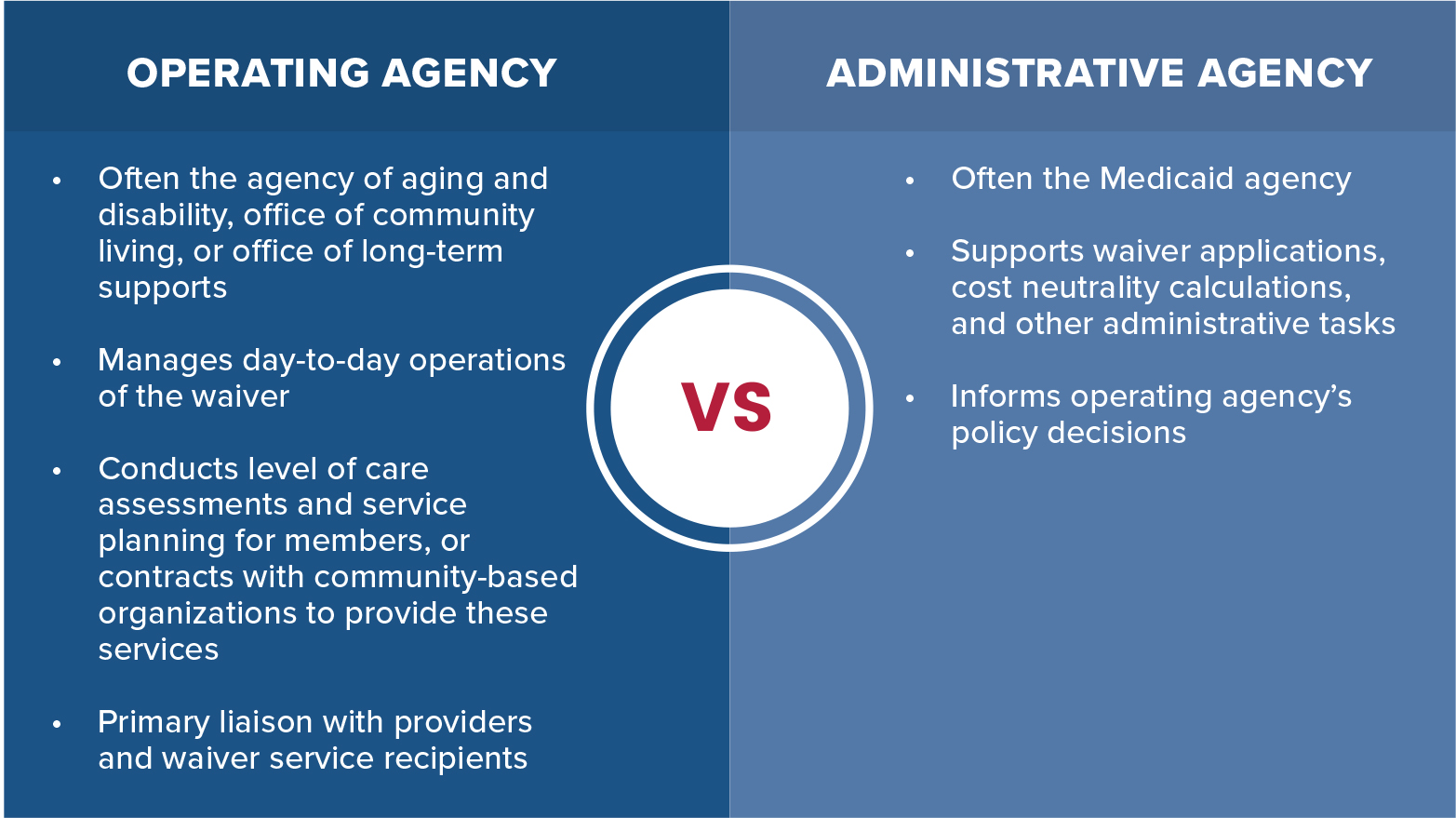

Although Medicaid is the primary payer for home and community-based services, Medicaid agencies are not the only – and often not the primary – state/territory agency overseeing long-term care services. Other state agencies and offices, including state agencies of aging and disability, elder or older adult services, and offices of community living or long-term supports, play a key role in HCBS policy and operations. As in other parts of Medicaid policy, there is substantial variation across states in the agencies or combination of agencies who drive long-term care policy and services.

Responsibility for HCBS waivers is typically divided between an operating agency and an administrative agency. The operating agency, which is often the state agency on aging and disability, office of community living, or office of long- term supports, is in charge of day-to-day operations for the waiver, including provider enrollment and contracting, level of care assessments for members, service planning, and liaising with members and providers. Sometimes, the operating agency will contract with another organization – such as an area agency on aging – to conduct assessments, coordinate care, broker services, and conduct monitoring. In contrast, the administrative agency, which is often the Medicaid agency, supports waiver applications and renewals, conducts required cost neutrality analyses, and supports applications for special funding, such as the Money Follows the Person program.

How does this impact how a person receives HCBS services?

Typically, an individual who is seeking care must apply for both Medicaid coverage and specific waiver services. Eligibility for waiver services often requires:

- a level of care assessment, which assesses an individuals’ needs and preferences and is typically completed by the operating agency or a contracted non-governmental organization; and

- an assessment of financial eligibility, which looks at an individual’s income and resources to determine if they are eligible for a specific waiver and is typically completed by the Medicaid agency.

After an individual is determined eligible for services, a case manager from the operating agency will initiate person- centered service planning. Person-centered service planning aims to collaboratively identify an individual’s strengths, goals, and preferences, needs for medical care and other services, and desired outcomes; the case manager then develops a care plan that identifies the services – including Medicaid-covered services and other services – that will be used to address any unmet needs. The case manager will also typically authorize a specific set of services (including the service provider and authorized hours of care) that can be billed to the Medicaid agency. After the individual begins receiving HCBS, their case manager stays in contact to address any emergent needs, revise the care plan when necessary, and conduct yearly reassessments. Although the exact services individuals receive vary dramatically across states, waivers, and populations, this person-centered service planning process always aims to honor individual choice, autonomy, and dignity.

What factors will impact the future of Medicaid HCBS?

Over the past two decades, the long-term care system has dramatically changed. In 2013, Medicaid spending on HCBS outpaced spending on institutional care, marking a significant milestone in efforts to rebalance the long-term care continuum. This milestone was the result of sustained efforts by advocates, policymakers, and providers to increase access to HCBS, and was catalyzed by the creation of the Money Follows the Person program in 2005 and the Balancing Incentive Program in 2010. In 2014, federal agencies created new standards for HCBS settings, with a focus on privacy, control of personal resources, and community integration. States are required to ensure that settings meet these requirements in order to continue receiving federal match, spurring improvements in HCBS quality. How might the HCBS system continue to evolve over the next decade?

Demand for HCBS is expected to grow as the United States’ population ages. The Population Reference Bureau projects that the number of Americans ages 65 or older will increase from 58 million in 2022 to 82 million in 2050. Simultaneously, the availability of unpaid family caregivers is expected to decline for a variety of reasons, including higher rates of childlessness, lower rates of marriage, and changing societal norms around unpaid caregiving. These demographic changes are expected to drive significant increases in demand for paid long-term care. Absent policy change to increase Medicare’s coverage of long-term care or to make private long-term care insurance more available, this increased demand will put additional strain on Medicaid programs.

Changes in the use of assistive technology in HCBS may help address these challenges. Remote patient monitoring, for example, allows providers to collect health data from HCBS recipients, such as vital signs and blood pressure. Medicaid was one of the first payers to allow coverage of remote patient monitoring for HCBS. Some Medicaid agencies also cover “smart home” technologies, such as smart speakers, automatic door openers, sensors on doors or stoves, and smart thermostats, which can help people with disabilities remain in their homes. Even with these technologies, however, many individuals who receive HCBS also need support from caregivers and direct care workers.

Serious workforce shortages threaten the ability of Medicaid programs to respond to the growing need for HCBS. Even with technological innovations, access to HCBS is ultimately dependent on the workers – including direct care workers like personal care aides, home health aides, and nursing assistants; direct support professionals; and independent providers employed through self-direction – who care for individuals receiving HCBS. The COVID-19 pandemic greatly exacerbated workforce shortages; in a 2022 KFF survey, all states indicated that they were experiencing shortages of direct care workers, and 44 states reported the permanent closure of at least one Medicaid HCBS provider. Even before the pandemic, there were longstanding challenges building an adequate HCBS workforce. Addressing this challenge will require sustained efforts from federal agencies, states/territories, and other payers to ensure that direct care is a viable career.

HCBS are, at their core, about helping people stay in their homes and remain connected with their communities. As the primary payer for HCBS, Medicaid plays a unique role in providing access to these services. The HCBS system was built, however, through action by people receiving HCBS and their families, advocates, state agencies, and federal policymakers. These partnerships will be essential to ensuring that the HCBS system can adapt to challenges, including growing demand for services and serious workforce shortages.

NAMD would like to thank ADvancing States and the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services (NASDDDS) for their insights during development of this brief. This resource was developed with support from The Commonwealth Fund, a national, private foundation based in New York City that supports independent research on health care issues and makes grants to improve health care practice and policy. The views presented here are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Commonwealth Fund, its directors, officers, or staff.

Related resources

Meet the advocate who has shaped Medicaid for people living with disabilities

NAMD Comments on Proposed Long-Term Care Minimum Staffing Standards

Stay Informed

Drop us your email and we’ll keep you up-to-date on Medicaid issues.