Why Did They Do It That Way? Program Integrity

Medicaid agencies use a variety of strategies to oversee providers and managed care plans, and to ensure that Medicaid members meet eligibility requirements.

Author

- NAMD Staff

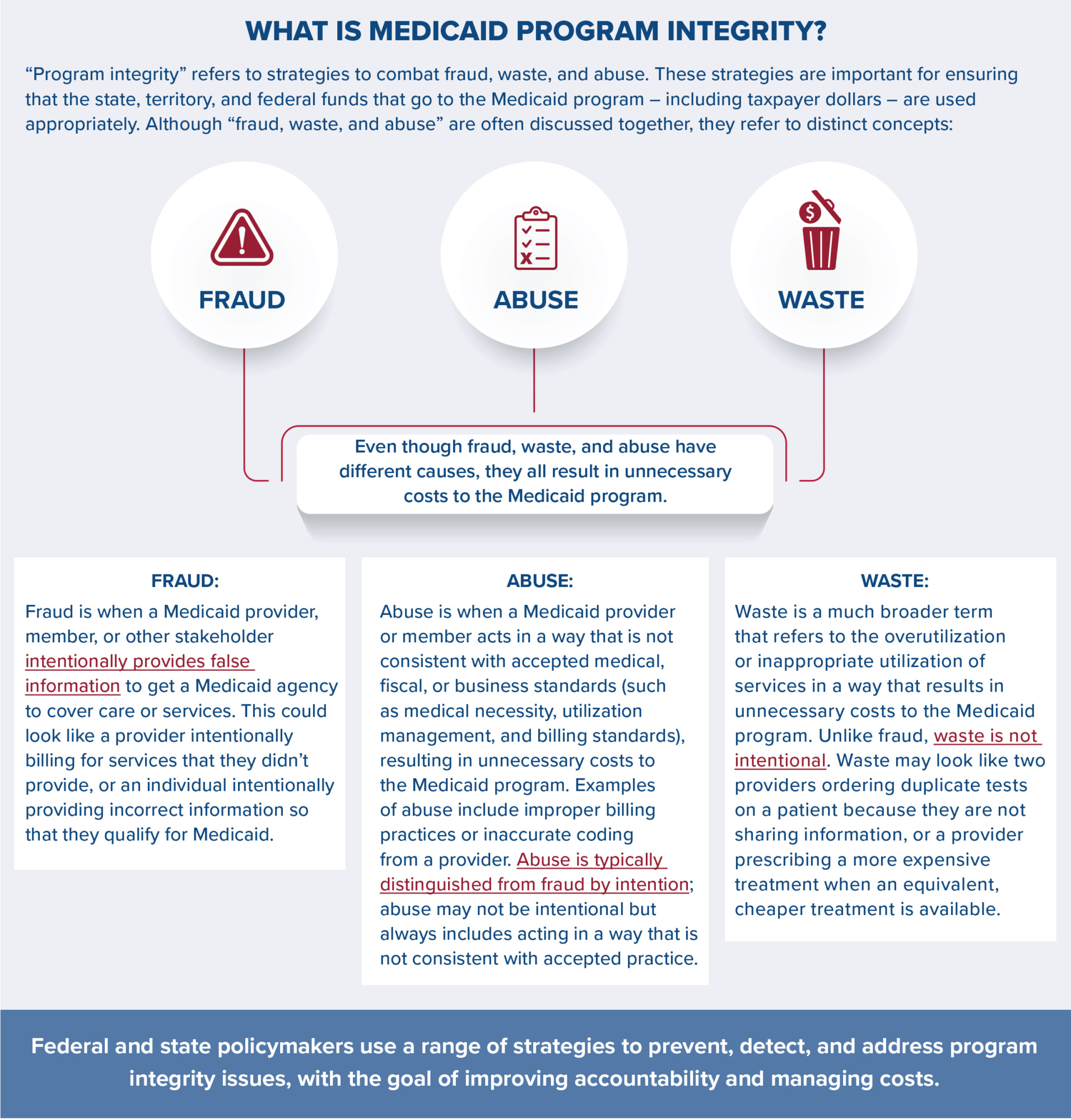

As of January 2025, Medicaid and CHIP (the Children’s Health Insurance Program) provided health coverage to 78.4 million people, and as of FY 2023, accounted for about $880 billion in total state and federal spending. Because Medicaid is jointly administered by states, territories, and the federal government, Medicaid agencies play a key role in preventing fraud, waste, and abuse in the program. As part of their core operations, Medicaid agencies use a variety of strategies to oversee providers and managed care plans, and to ensure that Medicaid members meet eligibility requirements.

How do Medicaid agencies and the federal government address fraud and abuse?

Unlike waste, fraud and abuse are addressed in federal law and can result in civil, criminal, and administrative penalties. States, territories, and the federal government each play key roles in detecting, investigating, addressing, and preventing fraud and abuse in Medicaid.

Detecting fraud and abuse

States, territories, and the federal government use a range of tools to identify potential fraud and abuse in the Medicaid program. These efforts include data analytics, audit strategies, and stakeholder reporting.

- Data analytics and surveillance: CMS, states, and territories use data mining and predictive analytics to detect unusual billing patterns, outliers, and service anomalies that may indicate improper activity. A key resource in this work is the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS), a standardized national dataset that includes eligibility, provider, utilization, and payment information.

- Audits and oversight: CMS and its contractors conduct audits of Medicaid agencies, managed care plans, and providers to ensure compliance with billing rules, service delivery requirements, and other regulations. States and territories also lead their own audits, often focused on high-risk areas such as personal care services or managed care payment structures. Federal entities including the HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) complement these efforts by conducting oversight of Medicaid agencies and CMS and recommending areas for improvement.

- Reporting suspected fraud: Medicaid programs rely on input from members, providers, and agency staff to identify potential fraud. Most states and territories operate fraud hotlines and online reporting tools to support these efforts. CMS, states, and territories also provide education to help providers and members recognize and report questionable activity.

Investigating potential fraud and abuse

When potential fraud or abuse is identified, Medicaid programs initiate formal investigations in partnership with state, territory, and federal entities.

- State and territory-led investigations: Every state (unless granted a federal exemption) operates a Medicaid Fraud Control Unit (MFCU), which investigates Medicaid provider fraud as well as patient abuse or neglect in health care settings. MFCUs are typically independent from the state Medicaid agency and often coordinate with state attorneys general, law enforcement, and federal agencies.

- Federal oversight and enforcement: At the federal level, CMS supports investigations through the Medicaid Integrity Program, which provides funding, guidance, and oversight tools to Medicaid agencies. Additional federal partners, including the OIG, Department of Justice (DOJ), and GAO, play key roles in auditing programs, pursuing enforcement under federal fraud and abuse laws, and evaluating systemic risks to program integrity.

Pursuing enforcement actions

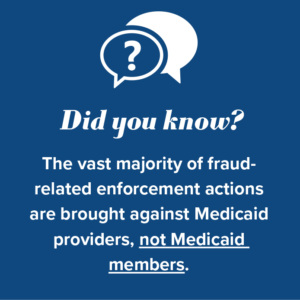

State, territory, and federal entities may pursue enforcement actions when they find evidence of fraud or abuse. Enforcement tools include a range of options such as recouping funds that have been improperly paid, monetary fines, and, in more serious cases, arrests and criminal convictions. Although fraud cannot be comprehensively measured in Medicaid, providers—rather than Medicaid members—account for the vast majority of fraud-related criminal convictions and monetary recoveries.

- Recoupment of funds. State, territory, and federal enforcement entities often pursue recovery or recoupment of funds that were acquired through fraud or abuse. In FY 2024, Medicaid Fraud Control Units recovered $1.4 billion in funds. Medicaid agencies also identify and collect overpayments to providers or organizations and return the federal share of these payments to CMS; overpayments can be the result of fraud, but are more commonly due to billing errors, incomplete documentation, or changes in eligibility status.

- Provider exclusions. Providers who are convicted of Medicaid or Medicare fraud are excluded from participating in federal health care programs. This means that the provider can no longer receive reimbursement from Medicaid, Medicare, or other federally funded health care programs. The OIG has discretion to exclude providers for additional reasons, including providing unnecessary or substandard services, submitting false claims, or losing professional licensure.

- Criminal or civil charges. Many federal fraud and abuse laws include criminal or civil penalties for violations. If a defendant is convicted of fraud, they can face prison sentences, fines, and civil monetary penalties. Providers who are convicted of fraud may also lose their professional licenses and/or be barred from future participation as a Medicaid provider.

Preventing fraud and abuse

States, territories, and the federal government take numerous steps to prevent fraud and abuse from occurring.

- Staff training. Medicaid agency staff receive training from the CMS Medicaid Integrity Institute and other organizations to learn about and implement best practices in program integrity. These trainings also cue Medicaid agency staff to emerging fraud schemes that may target their programs.

- Provider and member education. States, territories, and the federal government educate Medicaid providers and members on what constitutes fraud and abuse. For example, states and the federal government educate providers by distributing standards for providing Medicaid-covered services, offering training seminars, and developing toolkits. This education aims to ensure that providers and members understand their responsibilities, the laws governing fraud and abuse, and the potential consequences for breaking the law.

- Provider credentialing and enrollment. To provide services through Medicaid, providers must meet certain state and federal requirements, such as having applicable medical licenses. Medicaid agencies are required to use federal data hubs and formal enrollment and reenrollment processes to ensure that providers are eligible to participate in the Medicaid program. States and territories also check databases to make sure that providers have not previously committed fraud or been barred from Medicare or another state’s Medicaid program.

- Utilization management criteria. All Medicaid programs maintain utilization management standards such as prior authorization, diagnostic criteria, caps on type or frequency of services, and other tools to ensure that services paid for by Medicaid are appropriate and consistent with accepted standards of medical practice. Medicaid agencies develop and disseminate provider guidelines to inform Medicaid claiming.

- System edits. Medicaid agencies run Medicaid Management Information Systems (MMIS), which are IT systems that process providers’ claims for services and also include program integrity tools. States and territories use MMIS “edits”— or automated checks — to review claims before they are paid. These edits prevent Medicaid agencies from paying for claims that do not meet utilization management standards or otherwise appear inappropriate. For example, Medicaid agencies use National Correct Coding Initiative (NCCI) methodologies to implement procedure-to-procedure edits, which flag incorrect combinations of billing codes, and medically unlikely edits, which flag incorrect numbers of claims for a service (e.g., more than one appendix removal for the same patient).

How do Medicaid agencies ensure that enrolled individuals meet eligibility requirements?

While most Medicaid fraud and abuse is not perpetrated by Medicaid members, ensuring that individuals who are enrolled in the Medicaid program meet eligibility requirements is a core element of program integrity. Medicaid agencies use a variety of strategies, including electronic data checks and regular redeterminations of eligibility, to ensure that individuals enrolled in their programs meet eligibility requirements.

Federal law establishes minimum eligibility requirements for Medicaid. There are many factors that impact Medicaid eligibility, including citizenship, state residency, income, assets (for some coverage groups), and household composition. All states and territories cover certain mandatory eligibility groups, including low-income children, low-income pregnant women, certain parents and caregivers, and individuals receiving Supplemental Security Income, and can choose to cover additional eligibility groups.

How do Medicaid agencies make sure that individuals who are enrolled in the program meet these eligibility requirements? Under federal law, Medicaid agencies are required to check member eligibility when individuals newly apply for Medicaid and during annual renewals. Medicaid members are also required to report when they experience “changes in circumstances,” like changes in income, household composition, or residency, that may affect eligibility status.

Eligibility determinations are conducted by state and territory eligibility workers and by eligibility and enrollment IT systems, which check electronic data sources like the Internal Revenue Service and other social service programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. At application, states and territories check the information provided by applications against tax records, wage data, and other electronic sources to verify accuracy. If the information provided by the applicant is not “reasonably compatible” – or similar enough – to the data provided by these electronic sources, the applicant is asked to provide additional documentation. At renewal, Medicaid agencies are required to check these electronic data sources to see if they can automatically renew the individual’s eligibility before requesting additional documentation. This use of electronic data sources helps improve the accuracy of eligibility determinations, reduces workload for eligibility staff, and reduces reporting burden on Medicaid members.

In addition to these automatic data checks, states and territories use a variety of strategies to ensure that enrolled Medicaid members are eligible for the program. All Medicaid agencies use the federal Public Assistance Reporting Information System (PARIS), which indicates if a Medicaid member may be enrolled in two states simultaneously; this data can often lag by several months, however.

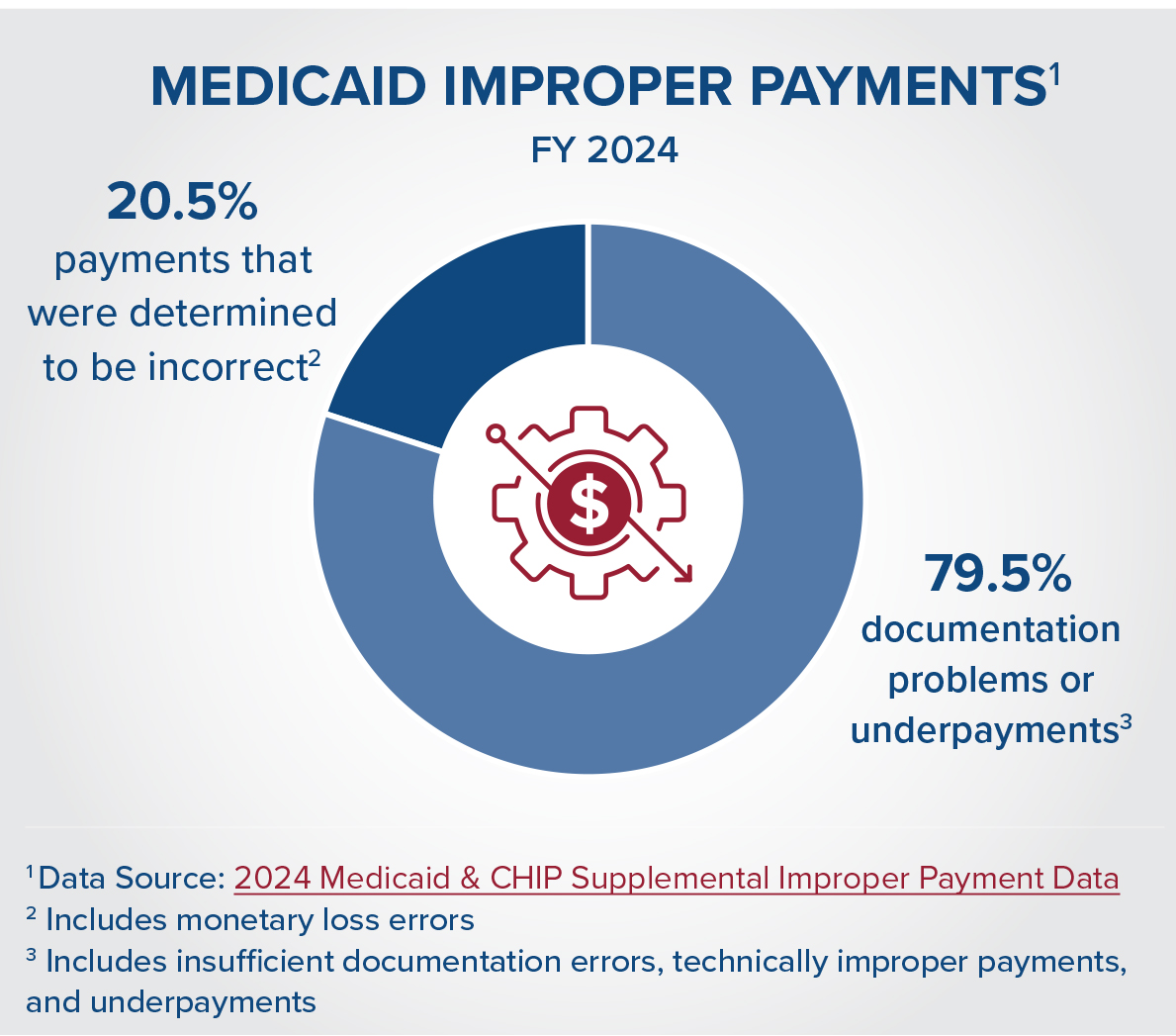

Medicaid agencies and the federal government also regularly audit eligibility systems for errors, including through the Payment Error Rate Methodology (PERM) audit. Although PERM is sometimes pointed to as a measure of fraud in the program, it is important to note that the majority of PERM errors are related to documentation issues, not fraud. For example, in 2024, about 74 percent of improper payments in Medicaid were due to insufficient documentation, meaning that HHS could not determine if the payment was corrector incorrect. Under current law, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) has the authority to withhold federal Medicaid payments if a state’s improper payment rate exceeds a 3% threshold, or to collaborate with the state on a corrective action plan to reduce improper payments. As part of these corrective action plans, states participate in the Medicaid Eligibility Quality Review (MEQC) program, which supports states in identifying and addressing the root causes of eligibility errors.

Finally, Medicaid agencies use strategies to identify if members have other sources of health care coverage, such Medicare, private insurance, or veterans’ health benefits. Medicaid is generally the “payer of last resort,” meaning that if an individual has more than one coverage source, their other insurer must pay for covered care before Medicaid will cover any remaining services. Medicaid agencies ask members for information about other forms of health coverage at application and renewal, and also use data matches to identify other sources of coverage. If a Medicaid member does have more than one source of health coverage, the Medicaid agency will coordinate with that other payer to ensure that claims are paid in the proper order.

How do Medicaid agencies conduct oversight of managed care plans?

Most Medicaid programs deliver care to members through contracts with private managed care organizations (MCOs). About 75 percent of Medicaid members are enrolled in managed care, under which MCOs receive a defined monthly payment amount for each enrollee, also referred to as capitation. In exchange, MCOs must provide necessary coverage and services for that enrollee. Because MCOs account for the majority of Medicaid spending and care delivery, oversight of MCOs is a top priority for states, territories, and the federal government.

Medicaid agencies use contracts to establish standards for managed care organizations. Under federal law, these contracts must include requirements that plans implement processes to detect and prevent fraud, waste, and abuse. These required processes include establishing compliance officers and committees, training managed care plan leadership and employees, and conducting routine internal audits.

In addition to these program integrity requirements, states and territories use a variety of tools, including ongoing monitoring of network adequacy, quality, and fiscal health, to ensure that managed care plans are following contract requirements and federal regulations. When Medicaid agencies identify issues, they use a variety of strategies to bring managed care plans back into compliance. These range from corrective action plans, which outline steps managed care plans need to take to resolve issues, to liquidated damages and financial penalties. In the most serious cases, Medicaid agencies can suspend payments to managed care plans or disbar plans from participating in the Medicaid program.

Medicaid agencies also use strategies to ensure efficient delivery of care through managed care organizations. These strategies include:

- Medical Loss Ratios and remittance standards, which measure how much of the monthly capitation payment that is paid to the managed care plan is spent on health care services versus administrative costs and profit margin.

- Quality withholds, which allow the Medicaid agency to withhold part of the capitation payment unless the plan meets certain quality targets.

- Risk corridors, which allow the Medicaid agency and MCO to split savings or losses beyond certain thresholds specified in the contract.

- Operational reviews and audits, which allow the Medicaid agency to review operational performance and identify areas for improvement.

What strategies do Medicaid agencies use to reduce waste?

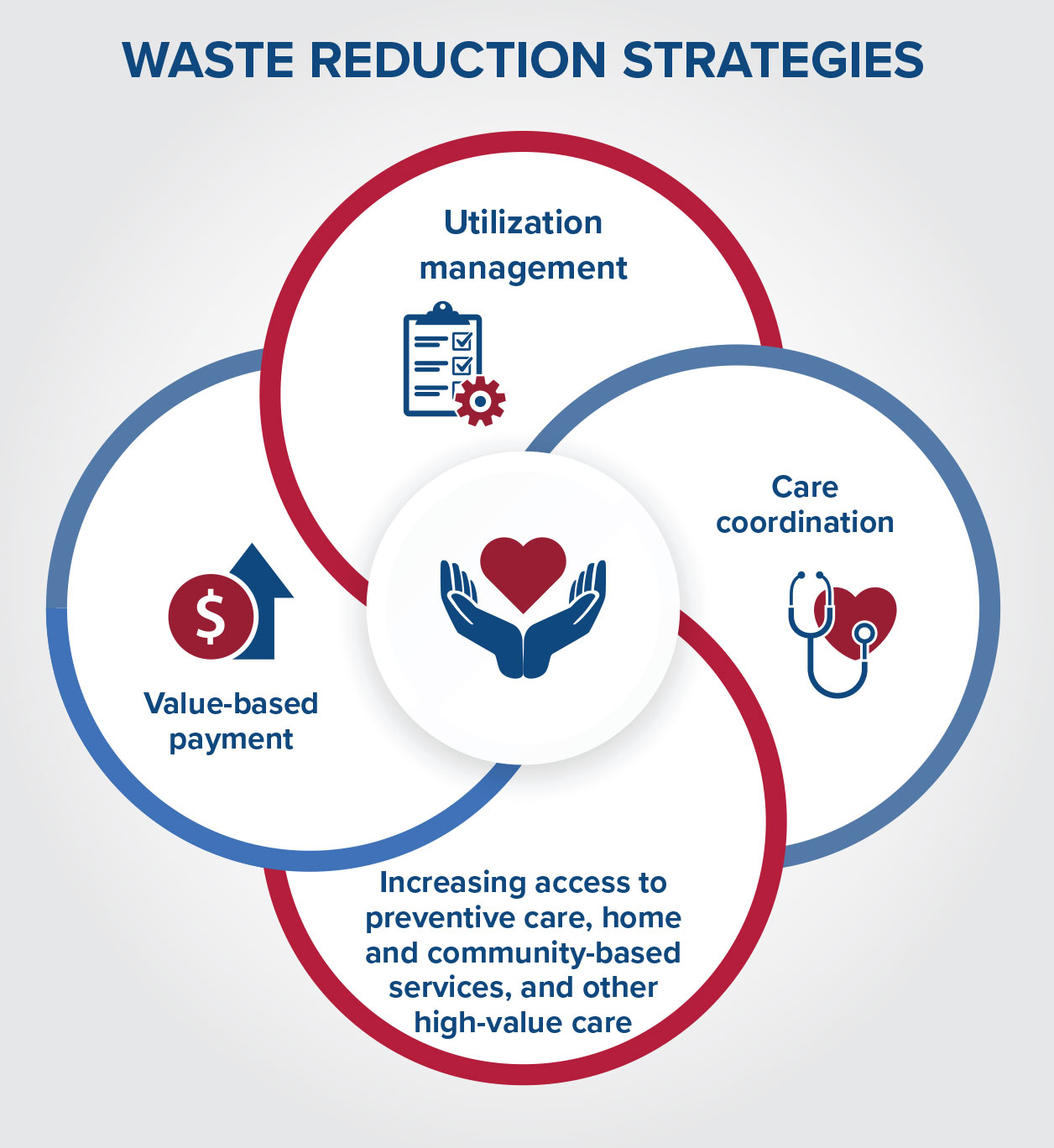

Waste is a much broader concept than fraud and abuse, and refers to duplicative or excessively costly care. Unlike fraud and abuse, which are defined in program integrity regulations and are typically investigated and prosecuted, waste is unintentional. Medicaid agencies and other health care entities are addressing waste through value-based payment, service delivery reforms, and care management strategies that aim to improve the efficiency of services and ensure they are appropriate.

Common strategies to reduce waste in the Medicaid system include:

- Utilization management: Like other payers, Medicaid agencies use utilization management strategies such as prior authorization to control health care costs and ensure that care is safe and effective. For example, a Medicaid agency may use step therapy, which requires a member to try a lower-cost, therapeutically equivalent version of a medication before covering the higher-cost version of the medication. Medicaid agencies also use concurrent and retrospective reviews to ensure that care delivered to a patient was high-quality, safe, and efficient.

- Care coordination: Medicaid members, like privately insured people, often receive care from multiple health care providers. Many Medicaid agencies and managed care organizations address the need to connect these providers by implementing care coordination strategies. Care coordination can help reduce duplicative tests and services, improve health outcomes, and reduce medication errors.

- Increasing access to preventive care, home and community-based services, and other high- value care: Medicaid agencies are focused on expanding access to preventive services, like high-value care vaccinations, screenings, routine checkups, and primary medical and mental health services. Higher utilization of preventive care may improve health outcomes and reduce the need for higher-cost health services like emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Medicaid agencies and the federal government have also made substantial investments in home and community-based services as an alternative to long-term institutional care. Home and community-based services tend to be more cost-effective than institutional care and are preferred by older adults.

- Value-based payment: States and territories are pursuing value-based care in their Medicaid programs to contain costs, improve quality, and align fiscal incentives with outcomes. In contrast to fee-for-service payments, in which a provider is paid a set rate for delivering a service, value-based payments explicitly tie payment to quality. For example, many states are using accountable care organizations (ACOs); providers participating in ACOs are held fiscally accountable for the quality and cost of care delivered to their patient population.

Conclusion

Fraud, waste, and abuse are distinct concepts, but all result in unnecessary costs to the Medicaid program. States, territories, and the federal government use a range of strategies to address fraud and abuse and to reduce waste. These programintegrity practices are crucial for ensuring that state and federal funds are used appropriately and efficiently.

Related resources

How Medicaid Provider Taxes Work: An Explainer

Medicaid’s Next Chapter

Stay Informed

Drop us your email and we’ll keep you up-to-date on Medicaid issues.