Top Five Medicaid Budget Pressures

This blog examines the current economic realities for Medicaid, highlights the top five external budget pressures, and explores the strategic responses states are adopting to control costs and sustain the program.

State and territory Medicaid programs are facing persistent and emerging budget pressures amid shifting economic and policy landscapes. As federal pandemic aid ends and tax revenues decline, these challenges become even more pronounced. Medicaid, which accounts for approximately 30 percent of total state spending in fiscal year (FY) 2024, is affected by factors such as:

- Federal Policy Changes;

- Prescription Drugs;

- Long-term Care;

- Health Care Labor Costs; and

- Program Administration.

This blog examines the current economic realities for Medicaid, highlights the top five external budget pressures, and explores the strategic responses states are adopting to control costs and sustain the program.

But first, how did we get here?

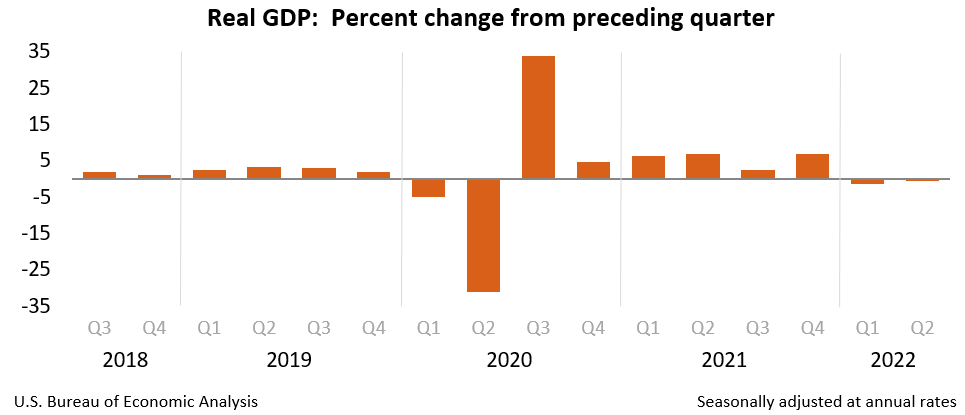

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, the U.S. rapidly plunged into a recession. The gross domestic product in Q2 2020 dropped by more than 30 percent from the preceding quarter, and millions of people lost their jobs. However, due to swift federal relief to states and localities, along with larger dynamics in the financial system, the U.S. economy quickly bounced back.

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis shows the realities of changes to gross domestic product through the pandemic.

Because of higher-than-expected tax revenue, along with an influx in federal funds, the state of state budgets remained strong throughout the public health emergency (PHE). For instance, fiscal year 2022 marked the highest year-over-year increase (16 percent) in general fund spending for over 40 years, and states experienced multiple consecutive years of widespread revenue surpluses.

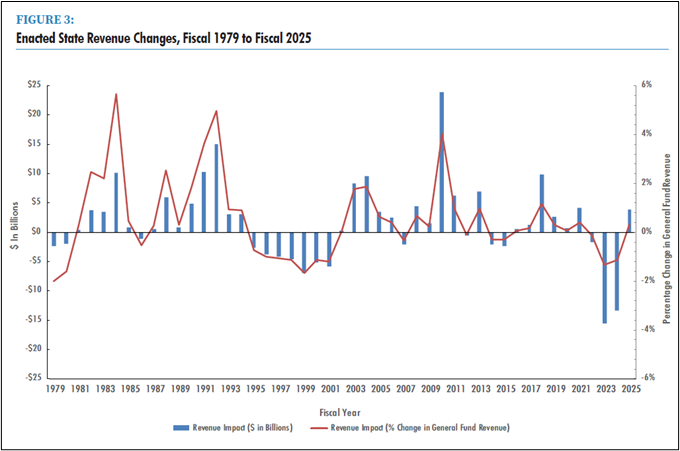

However, these dynamics that resulted in robust annual revenue growth started to shift in the last year. With the decline in federal funds, slower economic growth, and enacted tax cuts (see figure below), state revenue growth has slowed. For example, in fiscal year 2023, general fund revenues experienced a 1.2 percent annual decline, marking the first recorded decrease in actual revenue collections since the start of the pandemic, and the largest decline since the Great Recession. Since then, we’ve seen continued modest revenue growth, and in response, states enacted FY 2025 budgets that included fewer and more targeted tax reductions, and in some states, tax increases.

The National Association of State Budget Officers Fall 2024 fiscal survey of the states shows enacted state revenue changes between FY1979 and FY2025

Why Should We Care About Medicaid’s Budget Pressures?

So, as we transition into this new era of state revenues that won’t be as strong as they’ve been in the recent past, why is it important to consider Medicaid’s budget pressures?

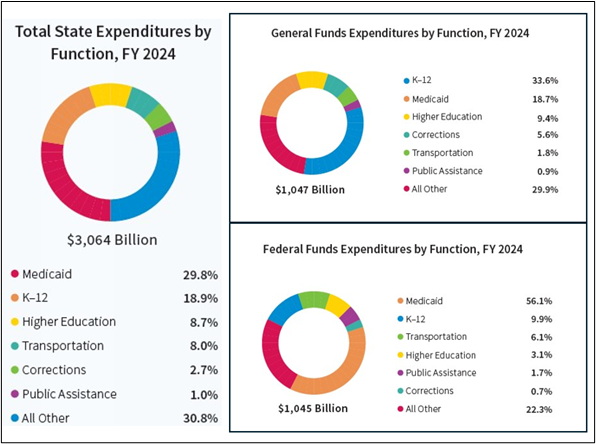

Well, Medicaid is a significant portion of the state budget, whether you measure that by the state’s general funds, the federal funds expenditures, or the total expenditures. Further, higher state Medicaid spending crowds out other needs for state spending (e.g. education, infrastructure). Notably, in FY 2024, total Medicaid spending grew by 5.3 percent compared to the prior year, and that spending accounted for:

- 29.8 percent of total state spending, which is the single largest component of total state expenditures;

- 18.7 percent of general fund spending, which is the second largest category of spending after K-12 education; and

- 56.1 percent of federal fund spending, which is the majority of federal fund expenditures by states.

The National Association of State Budget Officers 2024 state expenditure report shows state expenditures by function and by fund source (including general funds, other state funds, federal funds, and bonds)

The Medicaid program also produces a considerable amount of federal funding (i.e., FMAP) to cover health-related services in states. Generally, every state dollar spent on Medicaid yields anywhere between $1.00-$3.33 of federal funds depending on the state’s per capita income. And because Medicaid is an entitlement program, this federal funding is available for all eligible services for eligible populations.

**It should be noted that financing to yield federal funds differs for the territories than it does for states. The territories operate with an annual cap for federal funds. To learn more about Medicaid financing in the territories, click here.

We should also care about Medicaid’s budget pressures because of its role in the overall viability of the health care system, and because Medicaid is by law the payer of last resort. For example, Medicaid accounts for nearly a fifth of total health care expenditures in our country. In 2023, Medicaid was the largest source of revenue for health centers, the single largest payer for mental health services, and covered more than four in ten births nationally. And so, key providers in the overall health care system rely on Medicaid as an important source of revenue to keep their doors open.

That being said, the Medicaid program is already quite effective at controlling costs. The cost growth trend in Medicaid remains in the single digits and grows at a slower rate than both Medicare and private insurance. Further, Medicaid administrative spending represented 3.9% of program cost. Because Medicaid operates on such a lean budget, it can be difficult to find cost-saving opportunities. So, when external factors such as labor costs, inflation, and increases in enrollment related to economic downturns or pandemics pressure the Medicaid budget, state policymakers often have to make tough decisions (e.g., limiting services, cutting reimbursement rates) to find savings within the program. This is why fiscal viability for Medicaid is so important, and we know state policymakers are investing in an array of different sustainability strategies (e.g., investing in program integrity, preventive care, care coordination, value-based purchasing etc.) to insulate itself from these types of external factors.

Top 5 Medicaid Budget Pressures

Similar to state budget dynamics more broadly, Medicaid programs are facing tighter budgets this year as federal pandemic assistance expires, and tax revenue growth slows. The top five biggest Medicaid budget pressures are:

- Federal Policy Changes: Unwinding and Recent Congressional Activity

- Prescription Drugs: High-Cost Drugs

- Long-term Care: Long-Term Demographic Trends, Nursing Facility Costs, and Investments in Home and Community-Based Services Capacity

- Labor Costs: Workforce Shortages and Inflation

- Program Administration: IT Systems Expenses

These pressures are contributing to financial challenges. For instance, we saw a 16 percent increase in state general fund spending for the program in fiscal year 2024. So, let’s examine these pressures and what they mean for Medicaid and the overall state budget.

1. Federal Policy Changes: Unwinding and Recent Congressional Activity

Because the Medicaid program is funded and administered in partnership between state governments and the federal government, major federal policy shifts can put pressure on state and territory Medicaid budgets. We see this play out in both the unwinding and recent congressional activity around budget reconciliation.

States continue to feel budget pressures from the public health emergency and the unwinding, due to the unprecedented nature of these policies. These federal policy changes affected enrollment, caseload acuity, and revenue, all of which impact the Medicaid budget.

When Congress passed The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) in March 2020, it required Medicaid agencies to preserve Medicaid eligibility throughout the PHE for individuals who retained coverage during that time. This was in exchange for a 6.2 percentage point increase in their FMAP (i.e., enhanced FMAP or e-FMAP) . While the size of the program grew substantially, state budgets remained stable. This is primarily because the e-FMAP tied to this continuous enrollment requirement allowed Medicaid programs to cover millions of more lives (about 95 million lives at its peak).

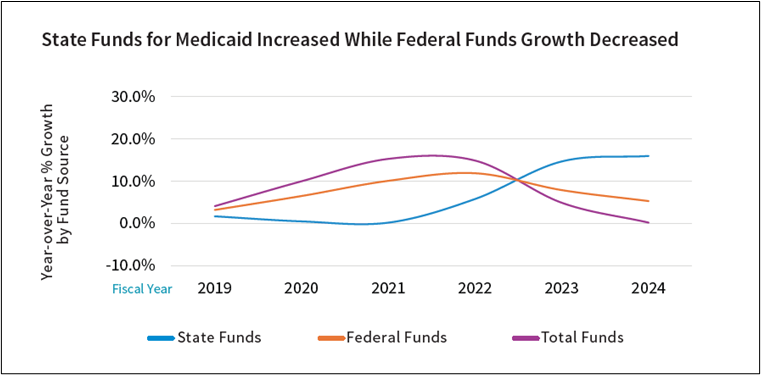

When the 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act passed, the legislation established a timeline to unwind the continuous enrollment requirement, resume normal eligibility operations, and redetermine eligibility for individuals who retained Medicaid coverage during the PHE. The unwinding also established a phase-down for this enhanced FMAP. Consequentially, the unwinding contributed to a reduction in federal funding to states. Federal funds made up 69.5 percent of total Medicaid spending in 2022. But, by FY 2024, federal funds made up 64.3 percent of total spending, which meant that states collected substantially less federal revenue for their budgets than they did in previous years.

The National Association of State Budget Officers 2024 state expenditure report shows year-over-year percent growth in the Medicaid program by funding source.

While unwinding contracted the Medicaid program by reducing enrollment, enrollment continues to be higher than pre-pandemic levels. Additionally, people who continue to be served by Medicaid post- unwinding have greater health care needs than those who retained coverage during the continuous enrollment requirement. Among many other reasons, including underlying trends in the health care system, this could be because:

- Individuals with health issues were more motivated to complete Medicaid eligibility forms and maintain health care coverage than counterparts without any health care needs.

- Once disenrolled, eligible individuals would only be incentivized to reapply and reenroll in the program after a medical event or an emerging medical need.

- Individuals who expect to be disenrolled by the program may be spurred to use health care services (e.g., fill prescriptions) before they lose access to Medicaid coverage.

Finally, many states continue to work through backlogs from the unwinding and therefore continue to see disenrollments and acuity shifts. Even states that have completed unwinding backlogs may continue to experience increased churn, which can contribute to unstable enrollment counts and more acuity shifts.

It may take months to even years to reach a steady state with respect to acuity and enrollment in the Medicaid program.

So, because there were various uncertainties on how federal policy could impact enrollment, caseload, and even financing, the public health emergency and the corresponding unwinding continue to pressure Medicaid budgets.

Negotiations over Medicaid policy in the 2025 budget reconciliation package pressure Medicaid budgets because states and territories face uncertainties around timelines, operational details, and policy that would ultimately inform how they would build these federal Medicaid proposals into state and territory budgets.

Congress is considering numerous policy proposals surrounding Medicaid, including, but not limited to, changes to eligibility policy, financing, and provider enrollment. States would need to consider the staffing and systems costs associated with implementation timelines. Further, these policies may have unpredictable impacts on enrollment and caseload acuity, which are both significant contributors to the make-up of a Medicaid budget. Finally, state-specific factors such as budget and legislative cycles, procurement policies, and local systems also play a crucial role in how quickly a state can adapt to federal policy changes. Since each state is structured differently, their ability to respond flexibly to new federal policies varies across the country.

Regardless of the policy, new or unprecedented federal changes can pressure Medicaid budgets by introducing uncertainty that would otherwise be considered during the budget development process.

2. Prescription Drugs: High-Cost Drugs

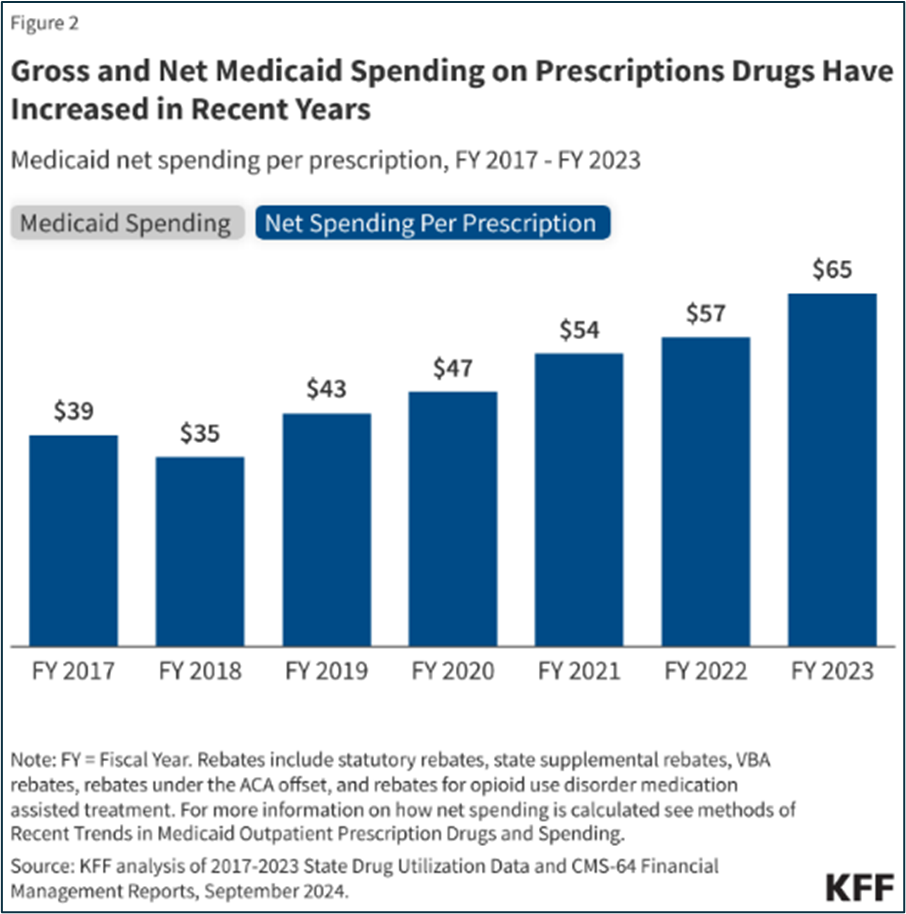

While Medicaid is very effective at controlling prescription drug costs compared to other payers, especially through the use of rebates, high-cost drugs do play an increasing role in pressuring Medicaid budgets. For instance, while the number of prescription drugs per enrollee decreased between FY2017 to FY2023, net spending on Medicaid prescription drugs increased by 72 percent during the same time-period. Again, this suggests the increasing role high-cost drugs have on prescription drug spending and state Medicaid budgets.

KFF Analysis showing net spending per prescription between FY2017 to FY2023

For the sake of this blog, we’ll examine how two treatments in particular (GLP-1 inhibitors and the new class of curative sickle cell therapeutics) increase spending in the Medicaid program.

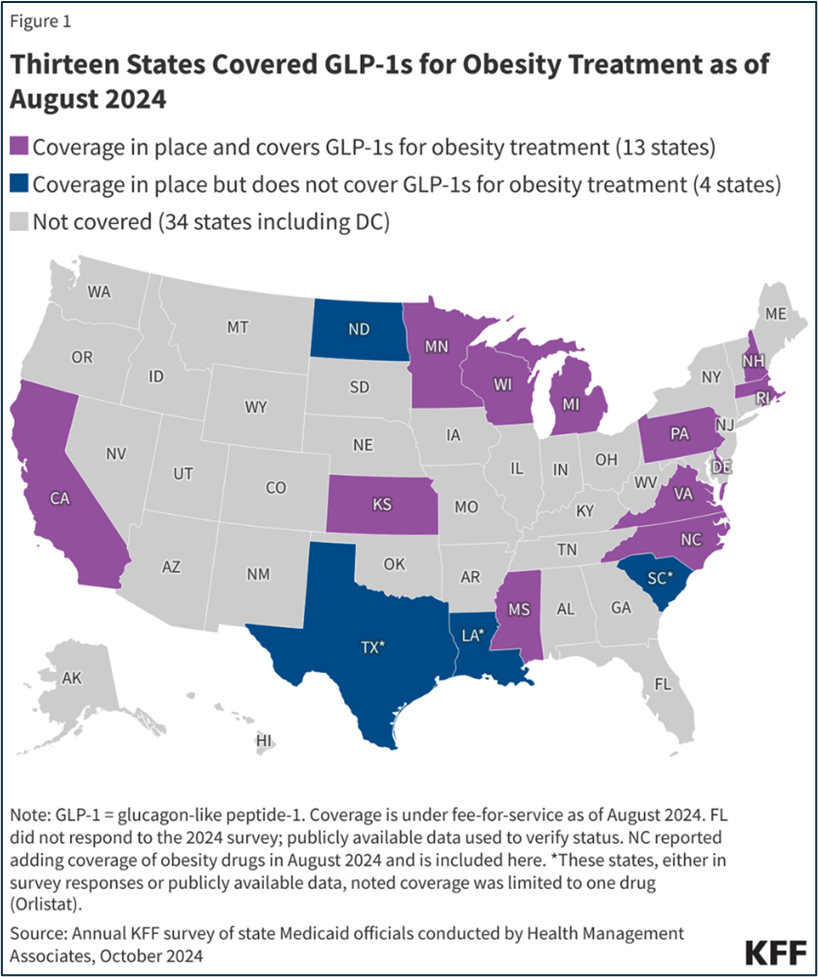

GLP-1 inhibitors are medications (e.g., Ozempic, Wegovy) that can support weight loss, treat diabetes, and/or heart disease, depending on the prescription. As of now, states generally do not have to cover this class of prescription drugs for weight loss under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, however, they are required to cover these medications for other Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved indications, such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease. There has also been considerable interest in covering GLP-1 inhibitors for weight loss because of their potential to improve health outcomes and save costs in the long term. For instance, access to GLP-1 inhibitors could prevent chronic conditions, hospital visits, and other acute care. However, given the realities of churn and access to these prescription drugs (impacts adherence for essentially a maintenance drug), that return on investment and improved health outcomes are not always immediately realized (i.e., outside of the one or two-year budget cycle). It’s too early to understand the long-term fiscal and health outcomes associated with covering these prescription drugs.

State reporting on anti-obesity drug coverage for obesity treatment from KFF as of August, 2024.

While it’s estimated these prescription drugs cost $900 per prescription before rebate, utilization is the driving force for costs. More than two out of five U.S. adults aged 20 or over are obese. From 2019 to 2023, the number of GLP-1 prescriptions grew by over 400 percent. Specifically, prescriptions and spending on Ozempic, which the FDA approved in 2017 for adults with type 2 diabetes, have grown significantly during this period, nearly doubling each year since 2019.

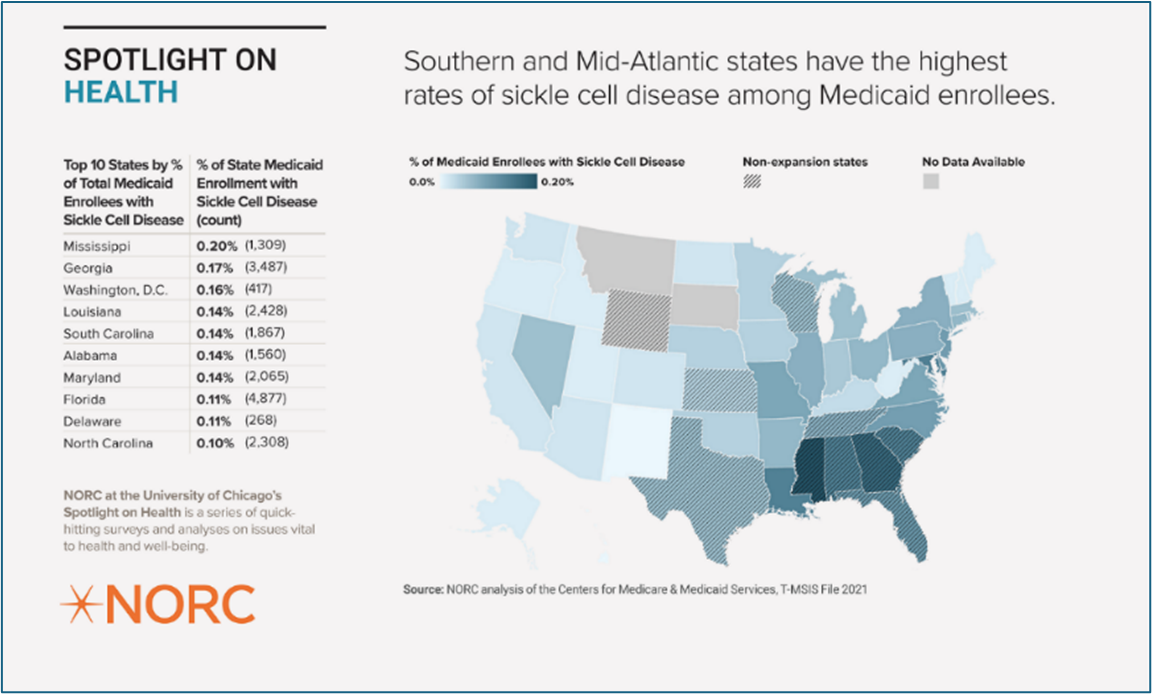

The new class of curative sickle cell therapeutics, unlike GLP-1 inhibitors, must be covered under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. Data suggests that Medicaid covers about half of all patients with sickle cell disease, and while estimates vary, over 50,000 people nationwide who are served by Medicaid have sickle cell. They are predominantly Black (67 percent), aged 21 to 45 (39 percent) and live in Southern and Mid-Atlantic states.

NORC data on the intersection of Medicaid members and sickle cell diagnosis.

These treatments are coming to market at $2.2 million (Casegevy by Vertex) and $3.1 million (Lyfgenia by Bluebirdbio) per person, which is similar, if not more than the disease-related medical expenses accrued over a single lifetime. Ultimately, this means that from a budgetary perspective, instead of paying for treatment over several decades, Medicaid would generally pay for a given treatment in a single budget cycle and potentially yield savings over several decades. Therefore, this class of high-cost drugs introduce a certain level of budget volatility, and we’ve seen Medicaid agencies leverage high-cost drug pools, risk corridors, and other financial mechanisms to account for the fiscal risks associated with inaccurate utilization projections. In addition, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Innovation Center recently launched a payment model around cell and gene therapies, which will first focus on covering these new sickle cell therapeutics to support states covering the treatment and associated services.

However, given the clinical risks, the limited provider pool that can administer these treatments, and the fact that the regimen essentially requires an individual to live at the hospital for several months, Medicaid may cover very few individuals for these treatments in the next few years. For instance, only about half of all states have at least one treatment center that can administer either Lygenia (approximately 50 qualified treatment centers nationwide) or Casgevy (approximately 35 authorized treatment centers nationwide). Ultimately, utilization will really be unique to each state, based on patients, providers, and other partners.

While this discussion is focused on sickle cell, over 600 cell and gene therapies were in clinical trials at the end of 2020. Research from Tufts Medical Center suggest that the number of new cell and gene therapies will more than double by 2032, implying that Medicaid programs have just begun grappling with coverage policy for high-cost cell and gene therapies.

To learn more about how these therapeutics intersect with Medicaid, check out NAMD’s blog: Cell and Gene Therapies: Excitement tempered by reality and Breaking the Bottleneck: Modernizing Medicaid Drug Access in the Million Dollar Therapy Era.

3. Long-term Care: Long-Term Demographic Trends, Nursing Facility Costs, and Investments in Home and Community-Based Services Capacity

Medicaid, not Medicare, is the largest payer for long-term care like home and community-based services and nursing facility care in our country. This means that changes to this part of the health care delivery system uniquely impact Medicaid. We are seeing long-term demographic trends, cost of nursing facility care, and building the necessary capacity in home and community-based services to serve people in the most cost effective and preferred settings pressure Medicaid budgets

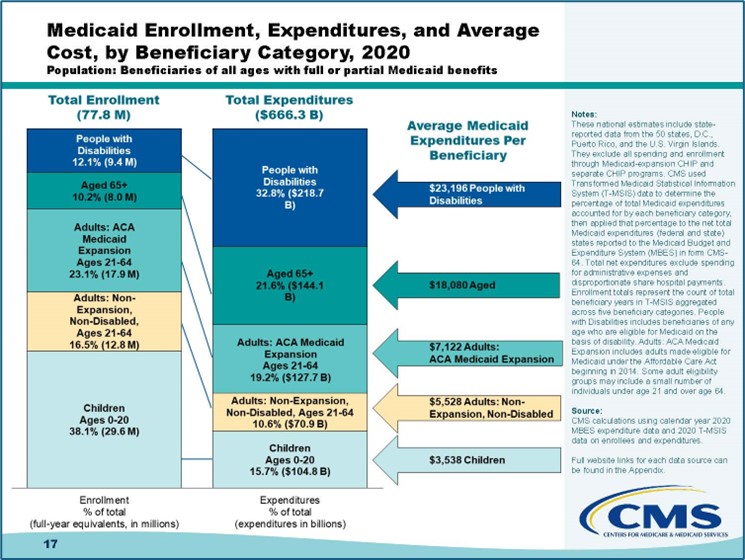

Long-term demographic trends contribute to increased budget pressures. As the single largest payer of long-term care, Medicaid will have to grapple with costs associated with a growing population of older adults that will require home and community-based services and/or nursing facility care in their later years of life. Approximately 33 million or 1 in 10 Americans are between 65-74 years old. That is an over 50 percent increase from 2010. In the next one to two decades, this group of individuals will likely require some level of long-term services and supports. And while only a small subset of them will be covered by Medicaid, increases in enrollment for this population will continue to pressure Medicaid budgets. For instance, older adults and people with disabilities, together, make up 22 percent of the total Medicaid membership yet, they account for over half of the total expenditures in the program.

CMS outlines the data around Medicaid enrollment, expenditures and average cost by member type in 2020.

Demographic changes impact Medicaid budgets now, and the magnitude of impact will only increase in the next few decades.

Increasing costs to cover nursing facility care continues to pressure budgets. For instance, National Health Expenditure (NHE) data showed a 9.5 percent annual growth rate for nursing facilities in 2023. KFF’s most recent annual budget survey also showed that over 90 percent of state respondents indicated they increased fee-for-services base rates for nursing facilities, and 16 states increased their supplemental payments for nursing facilities in FY2024. Typically, state Medicaid agencies pay for nursing facilities through a per diem rate based on underlying facility costs and/or prices that may include various adjustment factors accounting for inflation, acuity, geography, etc. More than two-thirds of states make supplemental payments to nursing facilities, which can be for many reasons, including supporting nursing facilities that play an important role in ensuring access to services in rural settings. There are many factors contributing to increased costs to cover nursing facilities, including but not limited to long-term pandemic impacts, workforce shortages in this sector, complex ownership structures within nursing facilities, and changing market dynamics. Given these different factors, we know many states are developing value-based payment strategies to align financial incentives towards better access and quality.

Building the necessary capacity in home and community-based services to serve people in the most cost-effective and preferred settings pressure Medicaid budgets. Over the past several decades, disability rights advocates, family members, and state and federal policymakers have pushed for greater access to community-based care, resulting in major shifts in the delivery system. Some of these shifts created new legal protections for people with disabilities to live within the community, and require state, territory, and local governments to reasonably modify their services to deliver community-based care. In every year since 2013, Medicaid spending on home and community-based services (HCBS) outpaced spending on institutional care, demonstrating the shift in the long-term care delivery system in recent decades. Member preferences to stay in their homes and communities, along with the more cost-effective nature of delivering long-term care in the community (as opposed to institutional care) continues to drive this rebalancing effort. Even though HCBS is more cost-effective in the long run, influencing the long-term care delivery system to rebalance towards HCBS requires significant investments including, but not limited to workforce development, technology, establishment of new and relevant benefits.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government (i.e., Section 9817 of the American Rescue Plan) disbursed unprecedented levels of one-time spending towards this rebalancing effort. While some states initiated project-based work, nearly all states used a plurality of these investments on provider payment initiatives to stabilize the direct care workforce. These federal funds are set to expire soon (if not already expired) for many states, and Medicaid agencies will need to decide whether to continue those home and community-based investments, including pay increases for direct care workers, without that enhanced federal subsidy that was provided by the American Rescue Plan. The convergence of demand, rebalancing, and pricing influence care delivery for long-term services and supports, which ultimately influences the Medicaid budget.

4. Labor Costs: Workforce Shortages and Inflation

Critical health care workforce shortages compounded by inflation pressure Medicaid budgets through provider rate increases. To attract and retain the health care workforce needed to address shortages, states invest in the education and training pipeline as well as rates, wages, and fringe benefits for providers who serve Medicaid members.

- The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates a shortage of nearly 200,000 nurses by 2031

- The AAMC estimates a shortage of between 18,000 – 48,000 primary care physicians

- PHI estimates the direct care workforce will fall short of demand by nearly 9 million jobs from 2020 to 2030

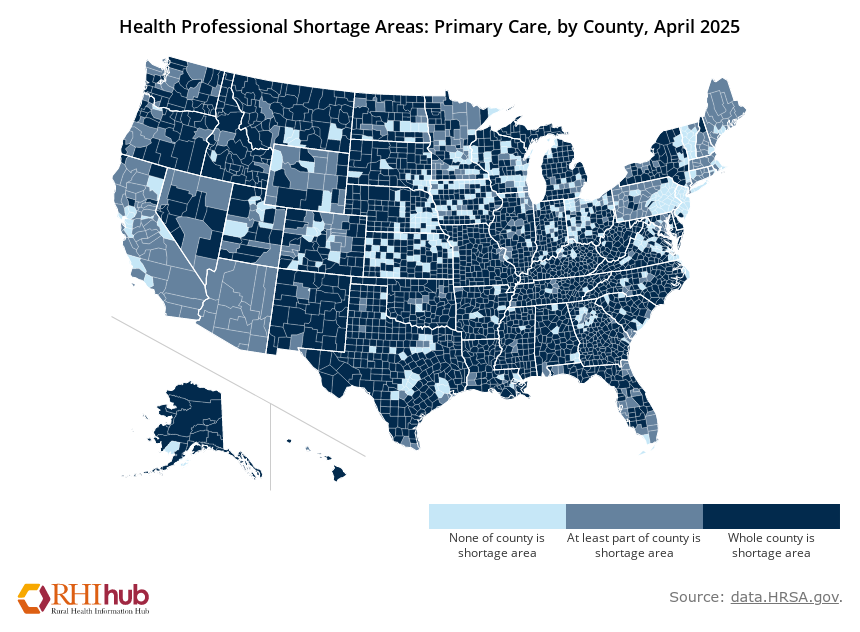

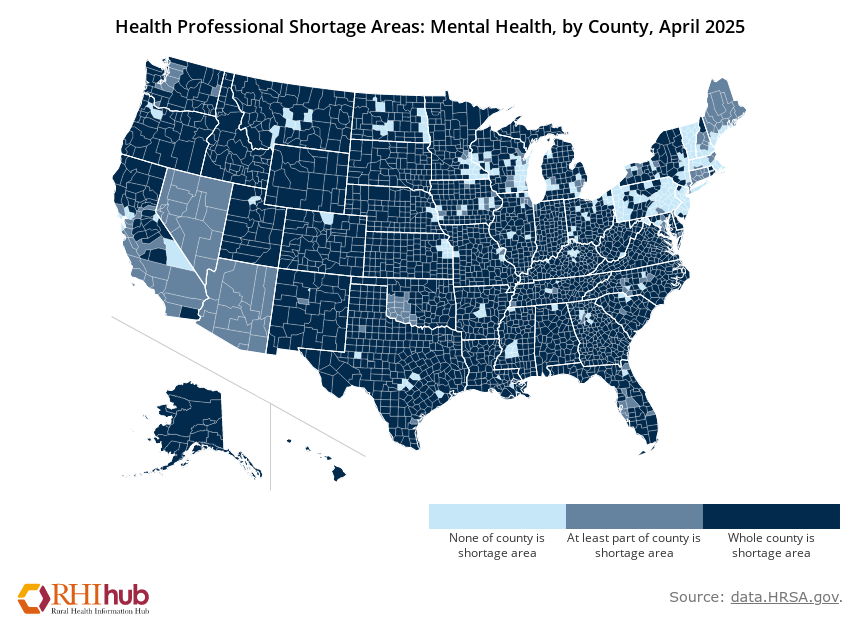

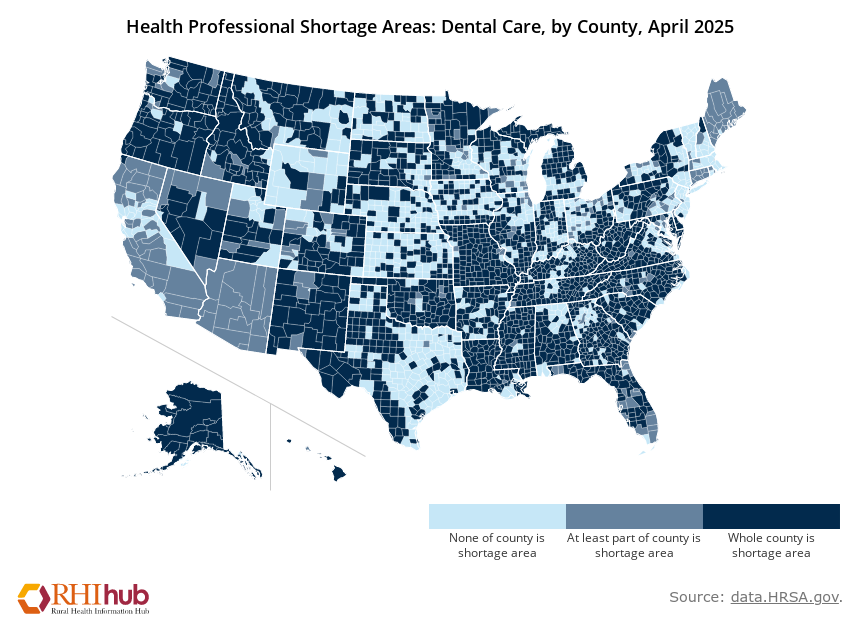

A robust health care workforce is a vital component to ensure access to care, and according to the Department of Health and Human Services, currently millions of Americans live in a health professional shortage area (HPSA). To support retention of health care practitioners and sustain safety-net providers with thin margins, Medicaid agencies have been increasing provider rates.

Rural Health Information Hub Analysis of Health Resources and Services Administration data on the realities of the health care workforce shortage.

Larger labor market dynamics also contribute to upward pressure on wages. For example, home health agencies and nursing facilities must pay more to compete with other sectors (e.g., fast food, retail, etc.) that employ low-wage workers. As a reminder, enhanced federal funds for home and community-based services will expire soon for many states (if not already), and so states will take on a bigger share of the costs associated with sustaining those rate increases.

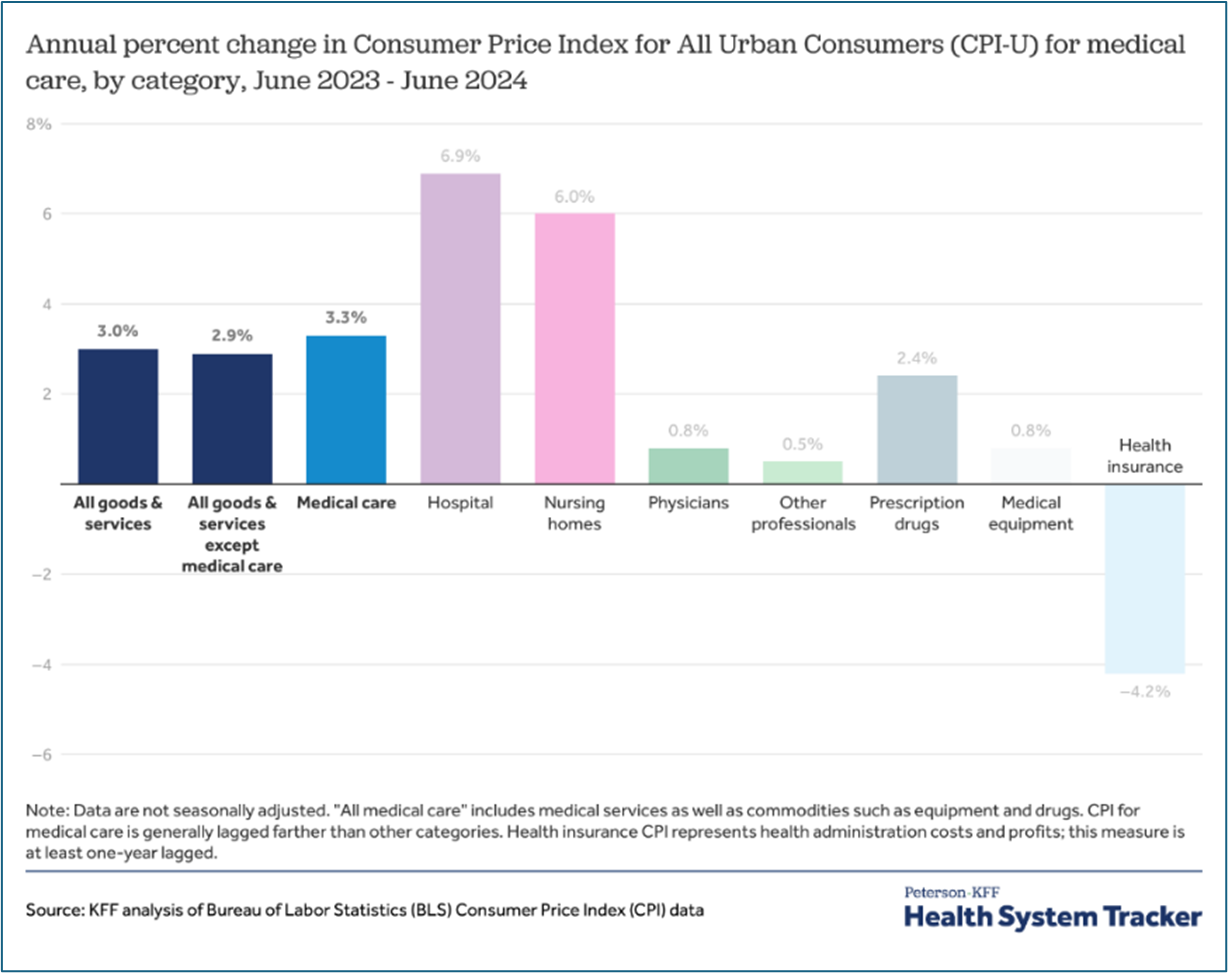

In addition to workforce shortages, inflation also pressures rates and state budgets. Medical inflation is consistently higher and increases at a faster rate than general inflation, resulting in ongoing upward pressure on the health care sector and Medicaid budgets. Further, inflationary rates are considerably higher among hospitals and nursing homes compared to general goods and services. Given Medicaid’s significant role in the health care industry, especially in long-term services and supports, it is particularly affected by these inflationary pressures.

The Peterson Center on Health care and KFF compares inflation for various categories of medical care

We know that many state legislatures are considering provider rate increases this session. However, with limited funds, states are prioritizing investments into parts of the health care delivery system where Medicaid has an outsized role (e.g., behavioral health, maternal health, long-term care). For example, we know some states are conducting comprehensive bench-marking studies, which can be incredibly complicated and labor intensive, to better allocate limited resources around provider rates.

5. Program Administration: IT Systems Expenses

An integral part of program administration, investments in technology can improve efficiency and agility in the Medicaid program, yet also pressure Medicaid budgets. While Medicaid administrative budgets are significantly smaller than private insurance, making up less than four percent of total Medicaid & CHIP expenditures, IT costs can make up a significant portion of the Medicaid administrative budget. This is especially true as states modernize key components of their systems through multi-year, complex projects. While the federal government generally provides higher matching rates for IT systems (e.g., a 90 percent FMAP for designing, developing, and installing IT innovations), states continue to feel pressure due to the large dollar volume of these projects, making it increasingly challenging for states and territories to capitalize on these investments.

Medicaid IT systems include the systems needed to determine/redetermine eligibility, process claims, and execute reporting and oversight activities, among other functions. So, investments into IT systems allow the Medicaid program to deliver on its commitments and ensure the most effective use of taxpayer dollars.

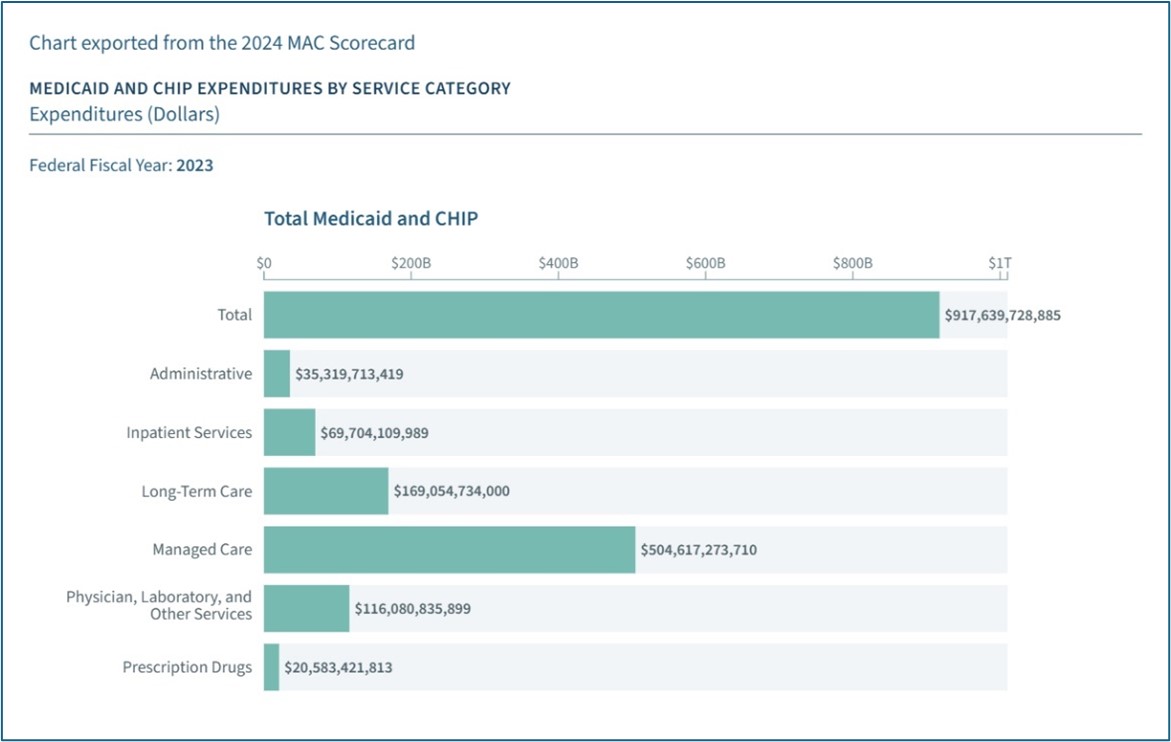

The Medicaid and CHIP Scorecard outline total expenditures by service category, demonstrating that the administrative budget makes up only four percent of total expenditures.

Because IT systems have been underinvested in the past several decades (many systems are still legacy systems from the 1980s and 1990s), Medicaid agencies continue to experience challenges in program administration, including but not limited to:

- Managing multiple competing priorities e.g., it can take a long time to make system changes in Medicaid

- Sharing data with key partners e.g., sister agencies such as child welfare, behavioral health, or even corrections

- Cybersecurity and protecting the state from bad actors

- Missed opportunities to streamline key administrative activities like vendor oversight

Medicaid programs have been making more investments into IT systems to address these longstanding challenges. But these projects are often complex and costly. In particular, the current market dynamics and lack of transparency challenge states’ ability to maximize value for the taxpayer dollar. In particular, because states don’t have full information on pricing, negotiating with IT vendors can be challenging. This information asymmetry can lead to multiple states, each paying the full price for the same IT solution, resulting in the vendor reaping substantial profits after they completed the initial systems upgrade with the first state (i.e., each state is paying “first dollar”). In addition, IT vendors may hold themselves out as able to deliver a solution but realize the complexity of doing so, once they begin the work, which often leads to many costly change orders.

We know many states are sharing information with one another and working with the federal government, including leveraging and maximizing the CMS’ Medicaid Enterprise Systems (MES) reuse repository to share documents, processes, information, and knowledge across states. This is all in order to ensure that prices for an IT solution are commensurate with the actual cost to develop them.

So, What Does It All Mean?

Moving into a tighter budget cycle, it’s important to note that it’s been five years since many states had to go through a belt-tightening season. Because there are limited levers that exist in the federal Medicaid framework to find savings, in very tough budget circumstances, states can be pushed to make hard decisions about:

- Who the program can cover;

- What benefits can the program cover; and

- How much can the program pay for these benefits.

So that’s why it’s important for policymakers to share institutional knowledge so they know which levers to pull during a tight budget cycle. It ultimately allows state policymakers to have the time, expertise, strategy, and member and partner feedback to make effective decisions that allow the program to control costs, promote access to care, and continue to deliver high-quality services.

To navigate those very tough budget situations, Medicaid and budget leaders are working to accurately inform projections and state budgets. For instance, some states use a consensus Medicaid forecasting process to ensure key policy and finance leaders inform the budget for the program. A small number of states have authorized the use of a reserve account into which federal Medicaid and/or shared savings payments are invested and can be used to ameliorate budget pressures. We are also seeing states control cost trends through strategies such as leveraging the CMS MES reuse repository, enhancing care management strategies, investing in program integrity, and establishing value-based arrangements to pay for prescription drugs and nursing facilities. States are also considering various strategies to address workforce shortages such as permitting delegation of tasks, using extenders (e.g., community health workers), and using telehealth. Beyond these immediate concerns, states are proactively undertaking recession planning efforts and examining underlying trends in the health care system, to prepare for future budget challenges.

Medicaid programs are facing significant financial challenges that require a multi-faceted approach. Understanding these pressures is the first step toward developing sustainable solutions. Continued monitoring and proactive planning will be essential to ensure the program’s long-term viability.

You can visit National Association of State Budget Officers and see all their resources as this overview was created in partnership with them. Their annual State Expenditure Report is an invaluable resource for understanding Medicaid and its impact on state and territorial budgets.

Related resources

How Medicaid Provider Taxes Work: An Explainer

Medicaid’s Next Chapter

Stay Informed

Drop us your email and we’ll keep you up-to-date on Medicaid issues.